Photojournalist Nickelsberg recounts challenges covering Afghanistan

By Lena Morris

While many other photojournalists would have feared or avoided reporting from Afghanistan during its times of violent conflict, photojournalist Robert Nickelsberg spent more than two decades documenting turmoil in that region.

As the school’s first Speaker Series of the semester, Nickelsberg spoke to a capacity crowd in the Ernie Pyle Hall auditorium Monday evening about the challenges of reporting from conflict areas.

“We’re honored to have such a veteran photojournalist who has been covering the country of Afghanistan for more than 25 years,” said professor Steve Raymer, who introduced Nickelsberg. He described the photographer as “a person who has labored to make sense of a country that’s been called the graveyard of empires, which in recent years has claimed the lives of 2,009 U.S. troops, more than 1,000 of our NATO allies and more than 10,000 Afghans.”

As a fellow photojournalist who experienced dangers in the field while covering Kabul in 1984, Raymer expressed admiration for Nickelsberg’s determination in returning to the battlefront.

“When I finished my assignment, I never looked back and never wanted to go back,” Raymer said. “We are in his debt for giving such a sustained, thoughtful and eloquent accounting of a time and a place that has taken such so much blood, treasure and emotional toll on the United States.”

Nickelsberg documented conflict areas all over the world as a contract photographer for Time magazine, The New York Times and others. During his talk, he showed selected photos from his new book, Afghanistan: A Distant War, which draws on his years of reporting. He said his mission was documenting not only the turmoil but also the civilians affected by the unrest.

“Who but the civilians are the ones who suffer the most in a civil war, particularly one that’s explosive and violent?” he said.

As Nickelsberg showed a picture of an Afghan family fleeing their home as civil war broke, quickly grabbing possessions that included a bicycle, a teacup, a chicken and some food, he spoke of the importance of capturing the people affected by the violence.

“Very often as journalists, if you don’t go to the front line, or if you do you don’t stay very long and it’s too much out of control, you quickly try to document what the effects are for the civilian population,” he said.

Photographing both the U.S. military and some of the most wanted war criminals in the region, Nickelsberg captured the challenges from a variety of perspectives. He said he wanted to emphasize the mountainous terrain of Kabul, which sits along the Himalayan mountain range and caused immense challenges for the U.S. military.

“I found there had to be a way to include geography in this book,” he said. Embedded with Marines, he saw them don steel vests and heavy backpacks to patrol the mountains.

“It was so challenging to walk up with 50 to 60 pounds of equipment and a rifle, and be expected to shoot, while the Afghans ran around in flip-flops,” he said.

A challenge of reporting abroad is understanding a country’s local rivalries, Nickelsberg said. Learning about the region’s past conflicts is not only crucial to reporting, but also to a journalist’s survival.

“That’s something that’s presented to you whether you go to Africa, Latin America or Southeast Asia,” he said, listing other areas he has covered. “You need to know the ethnic background of the place if there is a conflict going on. And that’s not so much a learning curve that you’re presented with, it’s also to help you survive. You don’t want to go to the wrong neighborhood.”

Nickelsberg said he first learned about the Soviets and Afghan native peoples in the late 1980s, when he first arrived in the region just as the Soviets were withdrawing after years of war in Afghanistan. From his long-time base in New Delhi, he periodically visited to cover Afghanistan’s civil war, the rise of the Taliban, the U.S. attacks right after 9/11 and current drawdown of troops from the region.

Nickelsberg said his job takes substantial emotional and physical strength. Sometimes, he trekked through harsh terrain for hours to shoot for just a few minutes. Other times, he witnessed violent deaths.

“There’s no triple espresso to get you going in the morning,” he said. “It has to come from within and the people you’re with.”

Nickelsberg said it’s unrealistic for photojournalists to act independently when working abroad. He said his key to survival depended on hiring the right crew to help him navigate through the foreign land.

“I’m very selective with the people I go out with,” he said. “That’s part of your day. I book the driver, the translator, in advance. You try to get the best people around you. They are the eyes and ears of the terrain.”

Nickelsberg allowed time for questions from the audience, which packed the auditorium and spilled over to Ernie Pyle Hall 214, where the talk was streamed on a large screen.

Several audience members asked about dealing with the trauma of covering death, violence and destruction.

“It does affect you to a certain degree, but when you live in this environment, you have a different threshold,” he said. “You try to resist collapsing emotionally. You must remain strong because the story needs to get out, and often when you come late into the situation, the only way to indicate that there was a violation of life is to show the dead.”

Whether documenting warring countries abroad or domestic issues, Nickelsberg said the fundamental duty of a photojournalist remains the same: to earn people’s trust and tell their stories.

“You must work on being able to integrate with people who don’t know you and to try to establish some level of trust,” he said. “Especially when you are a photographer that’s taking something from them, you have to make it feel as though it’s a cycle, that you’re also giving back.”

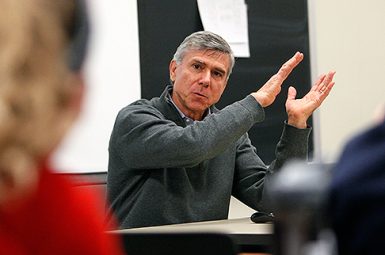

Nickelsberg arrived Sunday afternoon and has met with small groups of students and professors. Monday, he talked with Raymer’s J460 Reporting War and Conflict class, adjunct lecturer Chris Howell’s J344 Photojournalism Reporting class and Owen Johnson’s J448 Global Journalism class.

Tuesday, Nickelsberg was scheduled to have breakfast with a group of students and meet with professor of practice Joe Coleman’s J518 Reporting Global Issues Locally.

The next Speaker Series guest is Sage Steele, ESPN’s NBA Countdown host, at 7 p.m. March 24 at the Buskirk-Chumley Theater. All Speaker Series events are free and open to the public.