Photographers describe projects to save lost history

Sites of major battles and important events are often marked with plaques and museums, but for every recognized historical site, there are dozens of others that are unknown or forgotten.

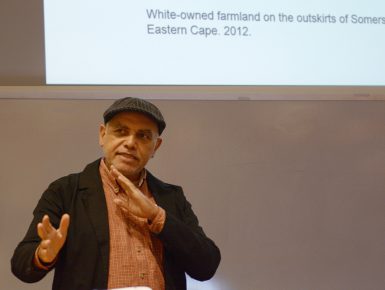

The Center for Documentary Research and Practice presented work by photographers Cedric Nunn and Andrew Lichtenstein in uncovering history’s lost relics and immortalizing them in black-and-white landscape photography during at talk Sept. 24.

The presentation, “Landscape | Memory | Trauma,” was the first of the new center’s speaker events. It was established last summer to provide faculty and graduate students resources to produce documentaries as part of their studies.

The two photographers conducted master classes separately, then presented their work during an afternoon session at the School of Education.

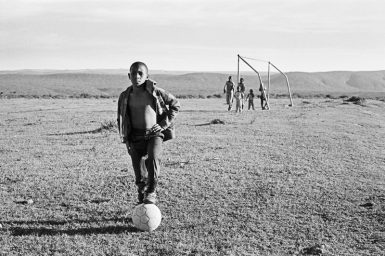

“My impetus with this project wasn’t to do good,” said Cedric Nunn, a South African. He uncovered historic sites, from fields to forgotten ruins, where marginalized people were defeated and forgotten by the apartheid government.

“I want us to be more awake and conscious of our history,” he added.

Nunn focused his documentary work on wars fought between colonial settlers and the native Xhosa people, which lasted more than a century. He went from village to village interviewing locals on where to find historic sites.

Nunn said he found that many of his colleagues were unaware of some of the atrocities committed by colonial settlers during the 19th century.

“How is it possible that a country can have a 100-year war and it not be something we live with?” Nunn said.

He found that although several ethnic groups in South Africa were not officially recognized by the South African government during apartheid, oral history led him to fields and forests, once the location of battles, towns and traditions now destroyed.

Andrew Lichtenstein didn’t know Cedric Nunn before the presentation, nor did they collaborate on their projects, but he said that it was uncanny how similar their findings were.

“This process of photographing isn’t an exact science,” Lichtenstein said. “But it’s interesting to me what gets marked, what doesn’t get marked, and why.”

Lichtenstein discovered unmarked Native American sites across the country. He said state laws that have been on the books for decades prevent them from being marked. Lichtenstein conducted research and interviewed area residents to discover locations of battles, lynchings and other events.

“I wanted to go to the sites that aren’t memorialized for one reason or another,” Lichtenstein said.

Nunn’s and Lichtenstein’s overlap in work came in documenting how people with power oppress minority groups. Lichtenstein said without collaborating, the two took some photographs that are “practically the same.”

Lichtenstein showed a photo of a memorial made in honor of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri. He said that he wasn’t sure it belonged in a collection of events in the distant past.

“How do you know when history becomes history?” Lichtenstein asked. “I don’t know.”

Nunn responded: “I think history is made, and it’s made in the present.”

Nunn said although his primary reason for making the photos wasn’t to do good, he feels his work is vital.

“I still don’t think there’s some good that can come of it,” Nunn said. “But I believe it’s better to expose something than to obscure it.”

More: