Downie weighs newspaper reporting’s challenges

By Greg Ruhland

Amid voters captivated by the upcoming presidential election, The Washington Post’s Leonard Downie startled some people in the audience when he announced he has not voted since 1984, when he supervised coverage of the Reagan-Mondale race.

“It’s important for me to have an open mind about the things we cover,” he told an audience Tuesday evening in the Buskirk-Chumley Theater. “If not, people could accuse us of bias.”

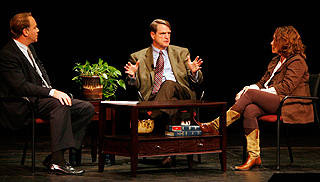

The former Washington Post executive editor’s discussed topics ranging from newspapers’ political endorsements to multimedia journalism to the challenges facing reporters who’ll cover the next administration during his free public lecture, which was the final speech in the IU School of Journalism Fall Speakers Series.

Downie, who retired Sept. 8, addressed questions from students and professional journalists Laura Lane, a (Bloomington, Ind.) Herald-Times reporter, and Indianapolis’ WTHR-TV broadcaster Ray Cortopassi.

Downie’s revelation about not voting surprised Lindsey Medlen, an Avon High School senior and Ernie Pyle Scholar applicant in the audience.

“Maybe he’s not voicing his opinion,” she said after the speech. “But it’s there.”

Downie abstains from voting and personally feels newspapers should not endorse candidates, though The Washington Post’s publisher disagrees. Still, the changing role of newspapers as “citizens,” he said, is to help the public decide its opinions by maintaining the strict separation between editorial and fact — a separation Downie likens to that of church and state.

After this year’s election, he said, a shifting news media will have the responsibility of scrutinizing the new president and Congress as they confront the economic, global warming, healthcare and other challenges of this century.

Doing so won’t be easy, but Downie believes journalists are “diggers of news, revealers of dark secrets, authenticators of facts, watchdogs of power and referees of arguments at a time of grave national challenges.”

His biggest concern? The fate of what he calls accountability journalism — the news that matters most to him. News like the Boston Globe’s 2002 exposure of clergy sexual abuse, or the Wall Street Journal’s coverage of unethical corporate backdating of stock options. Because this kind of reporting is expensive and time consuming, newspapers are cutting back.

Not all are, thanks to the Internet, which Downie said has expanded audiences and increased the impact of accountability journalism with its multimedia storytelling. And it’s given reporters more access to stories and reader tips. He thinks the Internet may even lead to TV news’ replacement down the road, as video from the Washington Post or other large news organizations rivals that of smaller TV teams.

“Journalists everywhere today are better educated, better trained, use better technology and work to higher professional standards than ever,” he said.

Lane and students weren’t so sure. They asked him if jobs would still be available, and Downie assured that many dismissed professionals have been older people. Up-and-comers who are willing to learn multimedia skills in a platform-neutral industry will be hired, he said.

Emily Brelage, another student who hopes to join the Ernie Pyle Scholars honors program, agreed with Downie’s predictions.

“I think media will be different,” Brelage said. “We have a bright future, but we have to be open-minded about how we are going to do journalism.”

Cortopassi questioned Downie on the challenges of overseeing Watergate scandal coverage. What began as a local Post story exploded onto the national scene, and “everybody was telling us we were wrong,” Downie answered. “The skepticism that exists now didn’t then.”

If anything rules his day, it’s quality reporting.

“The best writers are not people who just sit down and write beautifully,” Downie said. “They’ve done all the reporting, they have all those tiny details that makes for a very powerful description or narrative about an event that took place. The more you find out, the better judgments you’re able to make.”

One judgment he made involved a Danish cartoonist who put together a series of incendiary cartoons about the prophet Mohammed. The Post canned it.

Freshman journalism major Mitchell Blatt praised that decision.

“Whether to publish the Danish cartoon was noteworthy for me because it could have resulted in a lot of violence,” Blatt said.

In questionable situations, Downie asks himself three questions: Is the story true? Can it be proven? And is

it relevant?

Downie bemoans the lack of business journalists and foreign bureaus in the country. The Washington Post, he said, is now one of only a handful of American news organizations that still maintains a fully functional news bureau in Iraq.

He has plenty of reasons for hope, he said, and much of that rests with the many students in the audience.

“I owe something to journalism students,” he said. His advice? Build upon internships from one level to another, he told them. Hone your talent. Volunteer for free, if necessary. And know something very well, he said, besides journalism.

The author of four books and a 44-year veteran of the Washington Post, where his career began as a summer intern, Downie has been an investigative reporter, a metropolitan reporter and editor, and has held various editor roles before leading the paper as executive editor since 1991. Under his leadership, The Washington Post won 25 Pulitzer Prizes and many other accolades.

Though he’s left the day-to-day newsroom operation, Downie remains a vice president at large at The Washington Post Co.