Deford reflects on 45 years of sports journalism

By Paige Ingram

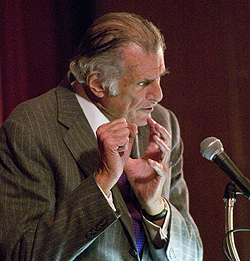

Just minutes into Frank Deford’s speech at Alumni Hall Wednesday night, he asked audience members for their trust.

“Trust me, ladies and gentlemen,” he said. “Nothing in life prepares you for talking with someone who is naked when you are not.”

Deford has had his share of less-than-comfortable interviews with sports figures during his 45-year career. He has taken the spotlight as a commentator on National Public Radio, correspondent on television, long-time sportswriter for Sports Illustrated, screenplay writer and novelist.

Deford’s visit marks the last lecture of the School of Journalism Spring Speakers Series. He spent the day lunching with area journalists and students and hosting an informal session in the library at Ernie Pyle Hall before delivering his talk, which was free and open to the public.

A near-capacity crowd listened as Deford wove his professional experience and personal views into an almost poetic narrative. In a gray pinstripe suit and bright purple tie, he spouted references from literature to music to religion. Yet, it was his laid-back demeanor and wit that drew in the crowd as he told stories of times past, complete with his own commentary on the situation.

“He was both informative and entertaining,” said IU student Tim Solon, a regular reader of Deford’s work in Sports Illustrated. “He said he didn’t want to name drop, but that’s what the crowd wants — the glitz”

And name drop he did. For nearly every sport, Deford had a personal story involving an iconic sports figure, ranging from basketball’s Jerry West to tennis’ Billie Jean King to basketball coach Bob Knight.

Many of these examples, he said, came from the time of sports journalism where, unlike today, athletes needed the press.

“We were more like fraternity brothers back then,” Deford said Wednesday afternoon during the gathering in the Ernie Pyle Hall library. He recounted buying players beer, told of times when baseball players worked “real” jobs during the off-season and recounted an era when writers had the kind of access to players that allowed for in-depth profiles.

For instance, players often welcomed Deford in the locker room during half time of NBA games.

“Not only that, but they’d bum cigarettes off of me,” he said.

He said with a sigh that times have changed for sports journalism. That elements of trust and dependency no longer exist between journalists and athletes. In a time when athlete have multimillion dollar salaries and agents and handlers, they don’t need “the ink,” he said, and don’t cultivate working relationships with writers.

Deford blames some of this trend on the journalists themselves.

“Everything is so successful. Everybody has learned how to do things,” Deford said. “There’s so much money out there that when things are good, the lid is on and nobody rocks the boat.”

Deford also criticized sports journalism’s focus on statistics over personality.

“Sometimes, we can just become numb with numbers,” he said. While watching the latest Masters golf tournament, he said he wished somewhere along the way someone would have supplied some biographical info about eventual winner Zach Johnson, until then a virtual unknown.

“That’s just not good journalism,” he said.

While Deford found success writing what he called “long articles about interesting people,” he realizes aspiring writers may not have that opportunity, thanks to today’s sports climate.

“The only way you can get that kind of access is to stay around and get that respect,” he said. “But I don’t know how you do that. You’ve just got to write better than anyone else or take pictures better than anyone else.”

It is the ability to write well that Deford seemed most concerned about in his speech Wednesday night.

“Words have been replaced so much by pictures,” he said of the technological advancements of journalism. “Even though we may use language more than ever (with e-mail), the weight of the word is lost.”

Despite his disdain of the predominance of highlight reels and athletes’ contracts that often shield them from the media, Deford still believes that sports matter. He cited his experience covering the 1990 World Cup in Cameroon. While not personally a fan of soccer, he said he was amazed at the unifying power the sport possessed for the poverty-ridden people of Cameroon.

“I never really understood the power of sports until that moment,” Deford said.

He urged the sports journalists in the audience to continue pressing for answers and the sports consumers to continue reading.

“Sports is now the lingua franca of the world,” he said. “Sports embraces us all.”