Scholars use oral history as research basis

Oral history is one of the oldest forms of storytelling, and it continues to be a viable and important part of media research.

Several school scholars use oral history – word-of-mouth recollections and reminiscences – as part of their research on several aspects of media, from the evolution of the TV news anchor to the history of a telecommunications organization, among others.

One boon to the use of oral history in research is the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ recommendation in September that oral history be excluded from scrutiny by institutional review boards, the bodies that regulate academic research involving human subjects.

IRBs are designed to safeguard people participating in studies that carry some amount of risk. If a team of researchers wanted to investigate the side effects of a new pharmaceutical, for example, they would have to get IRB approval before proceeding with their experimentation.

The reason for the recent ruling, according to a release from the Oral History Association, is that oral history already has an ethical code in which the subjects of the study, not the interviewers, retain the copyright until they say otherwise.

“Oral history is not a good fit” in the traditional IRB model, said associate professor Mike Conway, who relies on personal interviews for many of his journalism history projects. “It doesn’t really fit with what they’re trying to protect.”

The recent exemption news is a boon to researchers like Conway, for whom oral history work is inherently personal.

“It’s a wonderful type of research to do because of the connection you make with people,” he said.

His introduction to the practice involved just that kind of connection. Before enrolling in graduate school to become a media historian, Conway spent many years as a reporter, anchor and videographer for Midwestern television news stations. Making the transition to oral history as a graduate student at the University of Texas at Austin was a process of both learning and unlearning.

“It became an extension of being a reporter — and then having to learn the discipline of oral history, versus being a reporter,” he explained.

Conway’s introduction to oral history

Only a few weeks into his first term, Conway was sent to the archives to dig up information on Henry Cassirer, the first television news editor in U.S. history. He was surprised to learn that Cassirer was still alive. Not only that, but the archivist had his phone number. The next step was obvious. Conway bought a ticket, packed a camera and got on a plane. He landed in Annecy-le-Vieux, France, an alpine town closer to Geneva than Paris.

Conway encountered challenges in the field. Although he made some video recordings, the tapes were somehow damaged on the way home, perhaps by one of the sensors at the airport, and began to degrade almost immediately. Conway salvaged what he could but learned one of the first rules of oral history fieldwork.

“You have to expect technology to break,” he said.

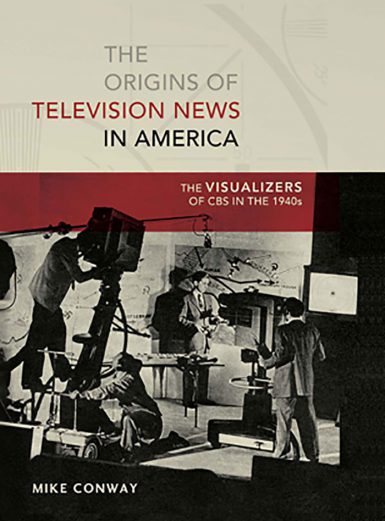

Despite the initial hurdle, Conway parlayed the Cassirer interview into a long-standing engagement with oral history that ultimately led him to The Media School’s journalism faculty. As a researcher here, he has published extensively on the subject. His 2009 book, The Origins of Television News in America, is shot through with oral history data, and a 2014 entry in The International Encyclopedia of Media Studies offers tips on how to conduct oral history projects ethically and effectively.

Mailland goes to the source

Assistant professor Julien Mailland made connections in Brittany, France, for a comparative history of the French company Minitel. For many years after its founding in 1978, Minitel led the world in online network technology. In 2012, it shut its doors, and Mailland attended the closing party to meet the entrepreneurs who had launched it more than three decades earlier.

Filling many pocket-sized notebooks during his research trip, Mailland compiled the history of Minitel, as told by those who ran it. His upcoming article in Annals of the History of Computing is a direct result of his observations in France.

Mailland’s rationale for choosing oral history as a methodology was simple. The data he needed lay at a party being held in northwestern France. So that’s where he went.

“Computer geeks and businesspeople tend not to archive things,” he explained. “So there is a lot of material that is disappearing at a rapid pace.”

Yang follows the story

Doctoral student Amy Yang specializes in ethnic media and immigration studies. Her experience with oral history involved the convergence of this specialization, a collaboration and her proficiency with language.

Before graduate school, Yang worked as a reporter in the Boston bureau of the World Journal, a leading Chinese-language newspaper in the U.S. While making her rounds, she often ran into David Li, a fellow reporter whose beat overlapped with hers. Li approached her about a project on Arthur Wong, a Chinese-American veteran who served in World War II. Yang immediately was interested. Younger Chinese immigrants have a broader, career-oriented outlook, she explained, while older immigrants like Wong have a more local perspective.

“They talk more about family,” Yang said. “We talk more about career.”

The result of Yang’s work is an oral history titled Late Glory: Arthur Wong and Chinese American WWII Veterans Who Liberated Europe, which she co-authored with Li. The 2014 volume recounts Wong’s experiences on the front, including his participation in the D-Day invasion.

Because Yang speaks Mandarin, her primary role in the project was to draft the questions that would be used during oral history interviews with Wong, who speaks Cantonese. For their work, the authors won a national award from the Chinese government. Yang said she’d like to work on a similar project for a domestic audience.

“That’s one of my dreams,” she said. “I wish I could bring more stories about that community to the U.S.”

‘Triangulation’ is critical

One of the allures of oral history is its potential for fostering intimate connections and producing good storytelling. However, the researchers also noted the importance of triangulation. Even though oral history is a valuable method, it’s not enough to produce good scholarship on its own.

“Doing oral history means asking people to reflect on things that happened 10, 20 or 30 years ago,” Mailland said. “People have false memories. They rewrite history.”

For this reason, he said, it’s necessary to triangulate oral history data with what can be gathered from archives or other sources. If interviewees give him conflicting stories about the same topic, he said, he lets it go.

“I don’t really talk about things I can’t triangulate,” Mailland said.

Conway echoed the sentiment. When a researcher triangulates different forms of data, he explained, it’s possible to allow oral history material to add color to the study through descriptions of scenery or anecdotal accounts of historical events.

“I would always say, go get as many sources as you can,” he said.

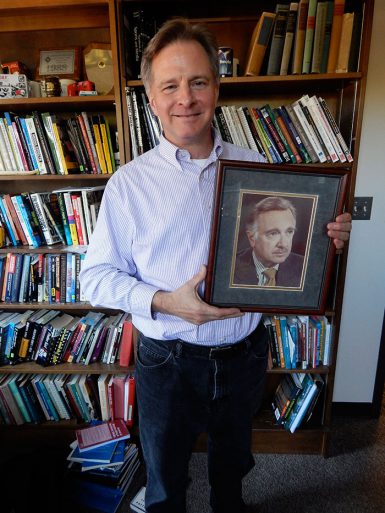

Conway’s office in Ernie Pyle Hall is a monument to this piece of advice. Media studies books line the shelves that take up two of the room’s four walls. Though perhaps more difficult to see, the oral history sources are present as well. One is attached to a framed photo that hangs inconspicuously between those two massive bookshelves. It’s of Walter Cronkite, one of the earliest and most respected TV anchors in U.S. history.

The photograph is marred by a pinprick just above Cronkite’s head. Conway explained that this comes from the thumbtacks he used to attach the picture to the wall at every job he’s ever had—a kind of journalistic guardian angel for television newsrooms.

The picture finally made its way into a frame after a once-in-a-lifetime encounter with the person it portrays. Cronkite himself signed the image while Conway was visiting him for an oral history interview. The gold ink is faded now, but the signature remains one of Conway’s favorite artifacts from the field.

The words exchanged during that interview speak to one of the greatest values of oral history data, Conway said. Because there might be only one shot to do an interview, and because sources might retire, move or even die, Conway urges all oral history researchers to remember: “There may not be other ways to get at those stories.”

More:

- Read about the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ recommendation to exclude oral history from scrutiny by institutional review boards.

- Learn more about the Oral History Association.

- Learn more about associate professor Mike Conway’s book, The Origins of Television News in America: The Visualizers of CBS in the 1940s.

- Read about the success of Amy Yang’s book, Late Glory: Arthur Wong and Chinese American WWII Veterans Who Liberated Europe.