Raymer’s retirement lecture emphasizes creativity, ethics

An FBI informant holds a syringe filled with a combination of heroin and cocaine to her neck in the women’s restroom of a federal government building, blocks from the White House.

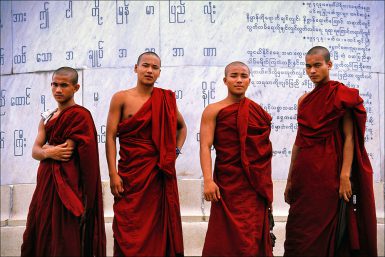

Young medical students from the European Union tend to dying women in a hospice in India.

Dozens of dirty-faced children gather around a pot of rice, waiting for their rations during a famine in Bangladesh.

Professor Steve Raymer shared these and other images with colleagues, students, family and friends at his lecture, “Somewhere West of Lonely: My Life in Pictures,” Friday in what he called his retirement lecture.

Raymer will retire this spring after 20 years at with IU journalism. Teaching was his second act; he spent more than 25 years as a photojournalist at the National Geographic before turning to teaching. He has taught visual journalism, media ethics, international newsgathering, and reporting war and terrorism courses.

Throughout his talk, Raymer stressed the importance of solitude and self-reflection to the creative process, advice that could apply to anyone in his audience, from his students to his fellow professors.

“In order to be really open to our creativity, we have to have the capacity for the constructive use of solitude,” said Raymer. “Artists and other creative people are often stereotyped as loners. While this may actually be true, solitude can be the key to creating some of our best creative work. We need the time for reflection.”

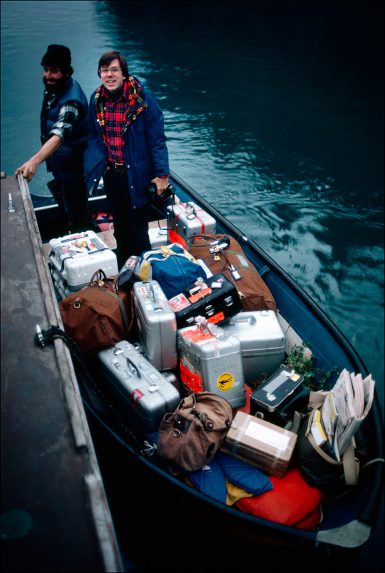

Raymer said covering the creation of the trans-Alaskan oil pipeline was an assignment that required this isolation. To portray the remoteness of the area where he was working, he showed the audience his photo of the dark blue sea with a long pipeline that stretched for miles, an image his colleague said looked “like a hair on a wedding cake.”

Raymer said resilience is an integral part of being a successful photojournalist, too. He told the audience his resilience was tested when he was victim of a terrorist attack at an airport while on assignment in Kabul, Afghanistan. After seeing a fellow traveler’s arm blown off by the explosion, Raymer had one night to recover before continuing his assignment.

While reporting on war-torn and hunger-stricken nations, Raymer said his ethical decision-making skills were tested as well.

“I always try to tell my students in my journalism ethics class how important the course is,” he said. “I tell them, ‘At some point in your career, you are going to be tested.’”

Since leaving his life as a photographer and editor for National Geographic, Raymer has continued working on his own creative projects. Redeeming Calcutta: A Portrait of India’s Colonial Capital, Images of a Journey: India in Diaspora and Living Faith: Inside the Muslim World of Southeast Asia all were published during Raymer’s time at IU. He said he hopes to take another trip to the United Kingdom in retirement to finish his forthcoming book, The Public House: An Enduring British Institution.

Raymer has collected several awards throughout his career, including The National Press Photographers Association Magazine Photographer of the Year Award, citations for excellence in foreign reporting from the Overseas Press Club of America and several first-place awards from the White House News Photographers’ Association.

He has taken his knowledge around the world, lecturing in places like Russia, China, Singapore and Vietnam, appearing on The Today Show, BBC radio and television, and Voice of America. He was awarded Columbia University’s DART Fellowship.

Raymer attributes his success to his perceptiveness.

“Creative people observe. Creative people see everything,” said Raymer. “They keep notebooks and sketchbooks. They see what others don’t see. They have the ability to break up the whole and see the parts, though we seem hardwired as humans to see the whole and not these important parts.”

In his introduction, former School of Journalism Dean Trevor Brown lauded Raymer’s ability to adapt and thrive.

“Accustomed to the esteem of peers, the resources of an iconic magazine, and the welter of news in Washington, D.C., Steve had to adjust to the rites of exploration by undergraduates in a public university in a small Midwestern town,” he said. “His work had ranged from gorgeous spreads on exotic places to unblinking witness to war and famine, disaster and suffering. He had taken shrapnel in his back and endured disease and fever. (At IU), many of his students had never left Indiana.”