Martin publishes book examining Stan Greenlee 1969 novel and screenplay

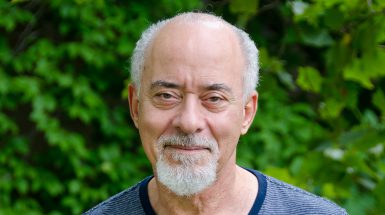

A new book by Media School professor Michael Martin, editor-in-chief of international film journal Black Camera, examines the Stan Greenlee novel The Spook Who Sat by the Door and the film of the same name from a racial perspective.

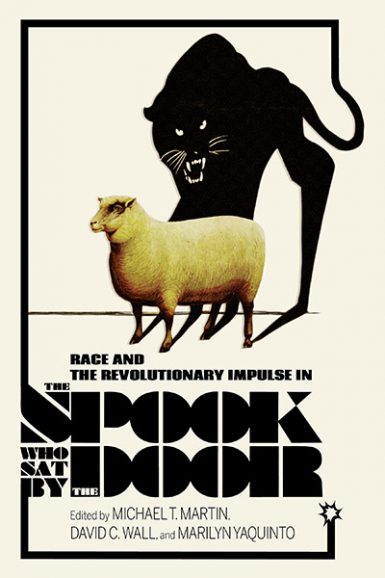

The book, Race and the Revolutionary Impulse in the Spook Who Sat by the Door, takes a comprehensive look at the innovative concepts and historical significance of Greenlee’s 1969 novel, which was adapted as a movie in 1973. Martin, former director of IU’s Black Film Center/Archive, uses interviews, essays, the movie’s full screenplay and press kit and more to examine the novel and film as they relate to race, class, social inequality and politics.

Greenlee’s novel is the story of Dan Friedman, a quiet and astute black man from Chicago’s South Side who is accepted to train at the CIA under affirmative action as the organization’s first black officer. Upon graduating, Friedman returns to his community and organizes gang members into an armed insurrection group with the intent of starting a fortified resistance in Chicago. The group in Greenlee’s novel was attempting to liberate the black community through armed struggle, a departure from what was happening in the non-violent civil rights movement of the ’60s.

“At this moment, the world was on fire,” said Martin of the era in which the novel came out. “With decolonization struggles, the Watts riots, the inner cities in flames and the Civil Rights Movement banging against a wall, African-Americans and communities of color existed in conditions similar to people living in the third world. They were contained in the inner cities and ghettos. It was also a period in which the black middle class was evolving.”

But unlike the popular Marxist orthodoxy that claimed that revolution would arise from the middle class, Greenlee’s revolutionaries came directly from the streets of these ghettos.

“The focus is not on the middle class, but black underclass,” Martin said. “Prostitutes, pimps, petty criminals. The chronically unemployed. This class of people were mobilized into becoming a revolutionary force.”

According to Martin, Greenlee gave this lower class of people, including women, a historical role in social change, similar to the characters of Gillo Pontecorvo’s 1966 film, “Battle of Algiers,” which chronicles the Algerian war against the French government in the 1950s and ’60s.

However, Friedman, the novel’s hero, asserts that the fight he is spearheading is not a race war.

“At the end of the day, he says what we struggle for is the right of self-determination. Freedom is not to be reducible to race,” Martin explained. “So, they must align with the white working class who face similar struggles. These struggles began in inner cities led by groups of African-American men and women and spread to form solidarity with whites who share similar experiences of oppression.”

Greenlee’s novel was first published in the U.S. by Richard W. Baron Publishing Co. in 1969 after being rejected by dozens of other publishing houses. A few years later, after being adapted into a screenplay, it was initially rejected by every production company in Hollywood. When it was finally picked up by United Artists, it was framed as a “black exploitation film,” as Martin puts it, in which it adhered to the conventions of a typical action/thriller movie and downplayed the revolutionary aspects of the story.

“It was all done as an action movie,” Martin said. “You don’t necessarily notice that this is a primer. It is almost an instruction manual on what techniques can be used to incite this kind of thing. You could miss all of that. So, it was put in context of a black exploitation film, but, actually, it was a revolutionary piece of work.”

Despite its innocuous exterior, the FBI, as well as both black and white politicians, picked up on the film’s politically controversial message and moved to have it removed from theaters.

Martin explains that the issues seen in the novel and film are similar to those addressed today with movements like Black Lives Matter. His book is intended to be a platform of analysis and criticism of race relations today through the context of these controversial works.

“The face of it suggests that substantial progress has been made,” Martin said of. “If you look at social factors, economic inequality, the racial segregation in schools that is still with us, social segregation in housing, voter suppression, gerrymandering, there are a host of defining factors that suggest that all the problems are still here, just as they were 20 or 30 years ago.”

Martin continued to explain why his examination of the book and screenplay is important today “The practice of disenfranchising African-Americans and others through all of that clearly indicates that at work is a process engineered and orchestrated to minimize and deny communities of color their basic political, civil and human rights. The Spook Who Sat by the Doorway resonates as much in the present as it does past.”