Digital access less than ideal in Indiana

By Craig Lyons, Samim Arif and DeJuan Foster

Want to contact the county sheriff’s office and find out what’s happening in your community? Are you curious if your local health department has received any food-borne illness complaints? Would you like to know what kind of deal the county has with a labor union?

Good luck getting hold of the records – or even getting a response. Nearly half of Indiana county agencies contacted failed to reply to such basic requests in a recent test of compliance with Indiana’s Access to Public Records Act. And reporters didn’t have luck getting responses in follow-up calls to a third of the agencies, either.

But on the other hand, of the agencies that did respond and did have records responsive to the requests, most were quite willing to provide the documents in an electronic format by email.

Those are the key results of a test of public records compliance conducted recently by journalists from The Media School at Indiana University in partnership with the Indiana Coalition for Open Government. The graduate student reporting team sought to discover how county agencies across the state would respond to requests made by email and seeking records in electronic formats.

Out of 90 agencies contacted for this story, only 48 responded to initial email requests for information. Ten other agencies responded to follow-up phone calls placed by reporters. Many of the agencies that responded — 33 — said they did not have documents responsive to the requests. But 17 agencies did agree to release documents, and 15 of those agreed to provide electronic copies of records.

For some officials, not accommodating a request electronically is kind of a subtle way to discourage people from making those requests,” said Steve Key, an ICOG board member and executive director of the Hoosier State Press Association.

Barriers to electronic access posed by the agencies echoed the issues encountered in 1997, when a group of journalists across Indiana banded together to test county agencies’ compliance with the Access to Public Records Act. The journalists visited all 92 counties in the state to request copies of documents in person and found lapses in municipal agencies’ compliance with the open records law.

Since that last audit of APRA compliance, the ability to request and access public information online has grown immensely. In Indiana, about nine out of ten people live in a household with access to a computer, and three-fourths of those households have high-speed Internet access, according to data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s 2013 American Community Survey.

People are looking for information online, said Indiana Public Access Counselor Luke Britt, and it’s worthwhile for government agencies to meet that demand.

“I think it’s going to be best practice moving forward,” Britt said. “I think it’s a wonderful tool for access.”

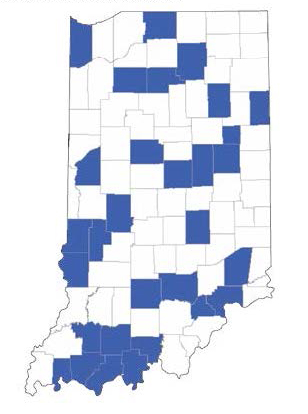

For the current audit, the IU Media School journalists set out to discover how effective online access is for requesters of public records. The team pulled a random sample of 30 of Indiana’s 92 counties and attempted to make requests by email of commissioners’ offices, sheriffs’ offices and health departments in each county. The requests sought to obtain union contracts from commissioners’ offices, 24-hour crime logs from sheriff’s offices and food borne illness complaints from health departments.

Law provides for electronic access

First passed in 1977, Indiana’s Access to Public Records Act includes provisions that relate to making requests electronically and obtaining electronic records. Britt said agencies must make reasonable efforts to provide electronics records to people who ask for them. And under the law, he said, public agencies must respond to electronic requests.

“There’s not a difference between a hand-written request for public record and an email request for public record,” Britt said.

Melinda Neeley of the Madison County human resources department is one county official who demonstrated an understanding of that. On April 10, Neeley received her first email request for information – ever. Still, she responded to the email from the IU journalists in the same way she would if the request came in person or on physical paper.

“The process is the same,” she said, and if a request is specific and the information is public, it’s given to the requester.

In all, 90 agencies were contacted for this compliance audit. In two counties — Jackson and Sullivan — reporters were told the commissioners do not have public email addresses. (An employee at the Shelby County Sheriff’s Department declined to give an email address, but the sheriff eventually did, though the department ultimately did not comply with the records request.)

Neeley’s department was among the 48 agencies that responded to email requests for information within the legally required seven-day window. The other 40 offices simply did not respond to the initial emails, which constitutes a denial of the requests under the APRA.

Reporters made follow-up calls to those 40 offices once the statutory time limit for responses was up; 30 agencies could not be reached or did not respond to messages left by phone. The other 10 eventually agreed to provide records. The reasons cited for not responding initially varied: Emails didn’t go to the right person, more information was needed or officials didn’t think they needed to respond.

In Kosciusko County, for instance, health administrator Robert Weaver said it’s likely no one in his department responded to the initial email because the agency hadn’t received any food-borne illness complaints as requested. His was among 33 agencies overall that reported they did not have the requested records.

Under the law, an agency is required to respond to a records request even if it does not have the requested records.

Britt said agencies can receive requests in any form – and can even ask for an additional form – though they must still respond to the initial contact as the law requires.

Of the agencies that responded to the records requests, four required an additional filing or records release form. Hamilton County’s health department required a form asking for the name of the record being requested, the reason for the request and contact information. Rather than specifying a reason, the team left that part of the form blank, prompting Jason LeMaster, director of environmental health for the agency, to email requesting that information. When asked why a reason was necessary, he did not respond, and the records request went unfulfilled.

At the Clinton County sheriff’s department dispatch center, the agency asked not only for a records release form but also a copy of an ID.

“That might be above and beyond what they can request,” Britt said.

According to the Access act, requesters also are not required to explain why they want a record, and if people request to inspect a record in person, they don’t have to identify themselves.

“As long as they have some way to follow up with you and get you the information, that’s good enough,” Britt said.

“Come down here and get it”

Beyond the difficulties in making records requests electronically, requesters of public records frequently report difficulties obtaining records in electronic formats.

According to Key, some public officials don’t want to go through the trouble of accommodating electronic requests or may not want to encourage people to get records that way. Instead, people must drive to an agency, find a parking spot, walk inside, get a hardcopy, pay a copy fee, go home and put the file into a computer, he said.

A bill that passed the legislature this year would have emphasized that agencies must provide records to requesters in electronic format if they are available that way. But Gov. Mike Pence vetoed the bill because it also contained a provision to allow agencies to charge requesters a search fee for public records.

Britt, however, said the APRA already requires agencies to make reasonable accommodations to provide electronic copies of documents and information under APRA.

But that doesn’t mean agencies always do that. Of the 16 agencies that agreed to provide documents requested by the IU reporting team, two refused to provide them in electronic formats.

Spencer County Sheriff Jim McDurmon was particularly rigid on this point.

“You said you want me to send it to you on the computer and I am not going to do that,” he said, adding that two attorneys told him he was on firm legal ground.

“If you want to come down here and fill out a form, I will give you whatever you want to know,” McDurmon said. “If you want to request it, come down here and get it.”

Britt said providing electronic copies of records depends on whether the requested information is scanned into a computer or already on one. Most sheriffs have information electronically, he said, and should make reasonable efforts to provide that.

“If they have it, they have to give it that way,” Britt said.

Although sheriff’s offices historically have been among the most difficult agencies in terms of public access, the IU Media School team found some of them to be very responsive to the public’s need for easily-accessible information. Sheriffs in Lawrence and Pike counties, for instance, took less than a day to send electronic copies of their daily logs – one hour and nine minutes in Pike’s case, to be exact.

And in St. Joseph County, the sheriff’s office has made it a priority to create a website and post information. Eric Tamashasky, legal advisor for the St. Joseph County Police Department, said information like daily logs used to be printed out and left in the lobby, so people would have to go to the office to look at the information.

“That seems ridiculous,” Tamashasky said, “so putting information online for people to see made sense.”

State statutes are clear about what information police departments have to release, Tamashasky said, and that’s why the daily log, jail bookings and information on active warrants are posted on the website.

The new normal

Despite the state and many agencies posting public information online, some local governments remain reluctant.

“There’s a kind of an old guard in some communities. They don’t want to put records online,” Britt said. “Newer progressive cities and towns, they recognize that’s an outreach tool, really, and they’ll leverage that to make those things available.”

For Indiana’s more than 2,200 municipalities, Britt said many places don’t have the technological capabilities to create websites and digital portals where minutes, budgets and other documents are posted.

“Sometimes, it’s just a matter of logistics where it’s impossible to do that,” Britt said.

At the state level, all agencies send information to the Indiana Transparency Portal and it’s all posted online, Britt said, and it’s a good idea for local governments to do the same. He said it will eventually become best practice.

“I think you’re going to see more and more of that,” Key agreed.

Part of being a responsible government steward is putting information out there and making it easier for the public to access it, Key said, and having documents online can save agencies time and resources.

Cities and towns are more often putting information online because it’s easier for them and their constituency, Britt said, and taking that step could reduce the requests they get for unequivocally disclosable information.

“I think there’s going to be a continuing trend for public officials to have certain basic information about their operations just posted on the website rather than forcing people to come in and ask for copies of it,” Key said.

More: