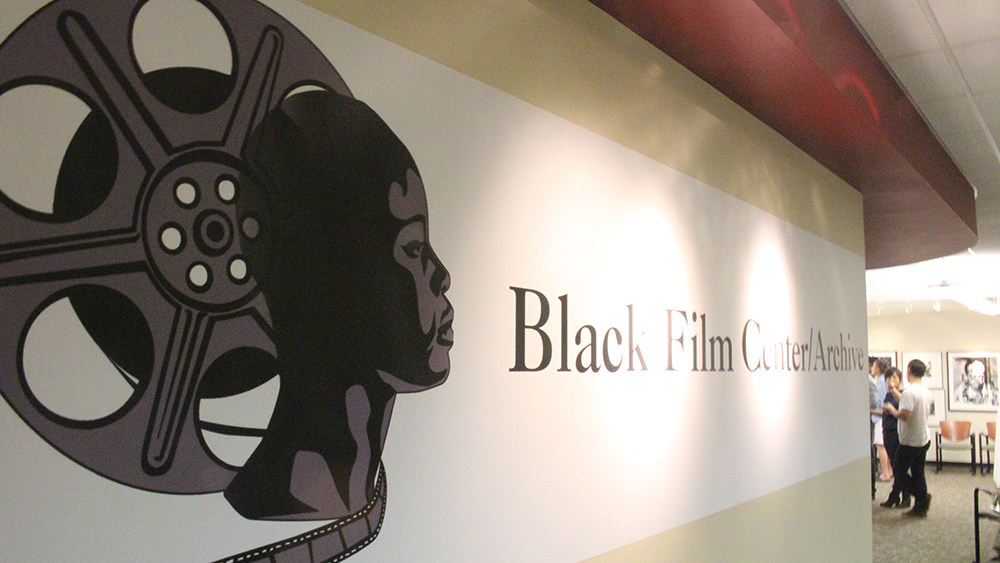

Black Film Center/Archive preserves film, sponsors programming

The IU Black Film Center/Archive hosted filmmaker Bridgett M. Davis and visual artist Renée Cox recently in recognition of Davis’ recent donation of her film, Naked Acts, to the archive.

The center celebrated the addition of the piece to its extensive collection with a screening of the film at the IU Cinema, followed by a series of talks and lectures by Davis and Cox.

But students and faculty wouldn’t have been able to see the film in its original form, or work with the artists who created it, if it weren’t for the BFC/A’s dedication to the preservation of film. Founded in 1981, the center aims to both preserve the work of black filmmakers and present programming about films and filmmakers, according to center director Michael Martin.

Michael T. Martin, Director, Black Film Center/Archive

And that’s one of, I think, one of the advantages of this new school. It’s going to create very interesting partnerships that will have, I think, a profound impact on how we study film and media at IU and our location in relation to the east and west coasts, where the primary film schools reside. The east coast, New York, Columbia, NYU, and on the west coast, USC and UCLA. So we’re really positioned, I think, geographically to claim the center as it were of the United States and to offer options to students nationally.

Produced by Bronson DeLeon

The talks by Davis and Cox are just one example of the programming aspect. The center also offers film screenings, talks and themed events, such as the Blaxploitation series this month.

But the preservation mission is what brought Davis to the center. Naked Acts, released in 1996, is one of the first films written, directed, produced and self-distributed by an African American woman.

“Self-distributed” is key, because that means it wasn’t marketed in traditional ways to a mass audience, Davis said during a talk at the IU Cinema after the premiere of her movie. Instead, she did the legwork to get the film shown in theaters. She then stored the film, which has been studied as an example of black feminism and sexuality.

“But then I got a phone call,” Davis said during a reception at the archives. It was from the archive storing the original elements of her movie. It was closing, and her footage — 26 reels of 35mm film, 12 rolls of Super 16 negatives and all of the promotional material — would be destroyed if she didn’t collect it. She briefly considered letting that happen.

But then she remembered reading about the Black Film Center/Archive at Indiana University.

“Bing, bing, bing,” Davis said of the moment she thought of a solution to her problem.

Davis emailed center archivist Brian Graney, explaining who she was and her situation. She not only wanted the center to preserve her materials, but she said she wanted to ensure that they would be accessible to researchers.

“That’s our function,” said Graney, director of public and technology services at the BFC/A. He manages the temperature-controlled vault nicknamed “The Fridge.” There, the center maintains a database of more than 8,000 works compiled since 1981. The collection also includes set props and one of the largest collections of African American cinema posters in the United States.

It’s located in the basement of Wells Library, but “Fridge” is a slight exaggeration. The room is just a bit colder than the offices and media reserve, but it operates independently from the power grid.

“If everything goes down, it’s supposed to keep working,” said Martin, who also is editor of Black Camera, an international film journal based at IU.

Martin is a professor in The Media School, and the center also is part of the new school established in July. Martin said this new partnership will give the center the resources to advance IU’s film programs so that they can compete with schools on the East and West coasts.

“That’s one of the advantages of this new school,” Martin said. “It’s going to create very interesting partnerships, and that will have a profound impact on how we study film and media at IU.”

“We’re really positioned geographically to claim the center, as it were, of the United States and to offer options to students nationally to study film,” he added.

The center already has been a magnet for students and researchers.

“I chose IU because of the Black Film Center/Archive,” said Nzingha Kendall, graduate assistant at the center who is studying black women filmmakers for her doctorate.

Kendall coordinates the film series for the center, but she’s specifically interested in conveying the diversity in both the African diaspora and IU.

“I think it’s important for people to realize its not just Spike Lee or Charles Burnett making films about black people or who are black directors,” Kendall said. “We really try to showcase the diversity of black filmmaking.”

Kendall said the center gave her the opportunity to work towards that goal.

“My first semester here, I had an idea for a film series, and Michael was generous enough to let me use this space,” Kendall said. “So over the course of a month, I showed four short films that dealt with black women and sex.”

“It’s interesting even today, right now, we’re still continuing in that tradition,” she added, referring to Davis’ Naked Acts screening.

Finding a home for her film at the center was “a very happy ending” for Bridgett M. Davis because it means her work will be safely preserved and studied.

“We have lost a lot of our history, haven’t we? So it’s important,” she said.