The Birth of a Nation symposium features discussion, screening

— with reporting by Sam Robinson

The 100th anniversary of arguably the most controversial film in the history of American cinema provided an opportunity for scholars, film studies students and area residents to discuss its artistic significance and its modern-day relevance during a symposium on the IU campus.

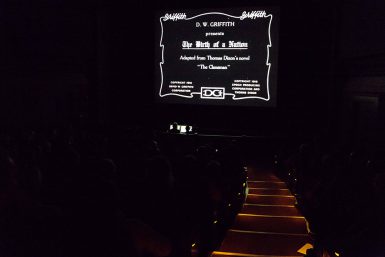

The school’s Black Film Center/Archive organized and hosted in partnership with IU Cinema From Cinematic Past to Fast Forward Present: D.W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation: A Centennial Symposium, Nov. 12-13. In addition to the public screening of the film with live piano accompaniment by Rodney Sauer of the Mont Alto Motion Picture Orchestra, the symposium featured two keynote addresses, three panel discussions and a roundtable.

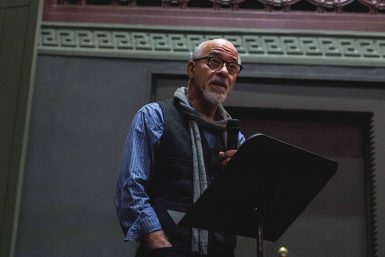

“The symposium was successful because it brought [to campus] an international group of prominent film scholars and historians who study and teach the film,” said Michael T. Martin, director of the center, in an interview after the symposium ended. “Having them together yielded new ways of thinking about the film in transnational and historical contexts, as well as its iterations in Hollywood film. And this was new.”

Praised for artistic innovations and sharply criticized for its racist theme, The Birth of a Nation depicts the end of slavery and degradation of white Southern society at the hands of former slaves. And, along with other historical fictions, it shows the Ku Klux Klan as a heroic organization that restores order and honor to the South against African Americans who are depicted as uneducated savages.

It was also one of the first films to be seen by a mainstream American audience, and it was a commercial success. The film was first screened in theaters across the country and seen by worldwide audiences of up to 200 million, and was shown to President Woodrow Wilson at the White House and members of the Supreme Court and Congress.

“It was the first blockbuster,” Martin told the audience before the screening on the first evening of the symposium.

He explained that the symposium’s goal was to study, not celebrate, the silent film, whose anti-African American themes continue to outrage.

“When it was first shown, and the decades that followed, it provoked all manners of mass protest as civil rights organizations mobilized against it,” Martin told the audience.

Melvyn Stokes, a professor of film history at the University College London and the president of the European association of film scholars, said the film was meant to reflect on an inaccurate version of history to inspire anti-immigrant, anti-African American change.

“It’s also taking refuge in the idea that this is history, and this is how things were 50 years earlier, but it’s not how it is today,” Stokes said.

The choice of actors in the film reveals director D.W. Griffith’s views about African Americans and the film’s deeply racist content, the speakers said. Whites in blackface played almost all major African American roles. African American actors were relegated to the background

“Seeing somebody on screen who was black actually chasing or even kissing a white woman would have had all sorts of legal problems,” said David Wall, an assistant professor of Visual and Media Studies at Utah State University. “For Griffith, the idea of giving any black actor a role that might constitute agency or power was not possible.”

Martin said although the film has historical inaccuracies that blame African Americans for failures of the Reconstruction Era, what the film doesn’t say is perhaps more powerful.

“It says nothing about how the commerce in slave trading in the North and the labor that provisioned cotton plantations in the South together generated great wealth upon which a planter aristocracy and northern bourgeoisie arose and prospered,” Martin said. “What we don’t hear are the historical factors in play that challenge the historical veracities of the film’s claims.”

While the film is historically inaccurate, it expresses how many Americans felt moving into the 20th century.

“Birth is about director D.W. Griffith constituting with the likeminded, and arguably the undecided, the vision of America,” Martin said. “Divided and embattled, yet poised for greatness, as it turned the corner and stumbled with great fanfare into the 20th century.”

The film screening was shown on the first evening of the conference. Earlier that day, Stokes spoke on “Transnational and Historical Perspectives.” The following day, University of California, Berkeley, professor emerita Linda Williams spoke on “Melodramas of Black and White and Early Race Filmmaking.”

“As controversial as Birth is and will continue to be, it has utility and is essential for teaching the history of American cinema,” Martin said after the symposium.

The symposium also provided a way to examine the film’s traces in contemporary cinema, reflected in films such as 12 Years a Slave and Django Unchained. It also showed how other countries and cultures viewed The Birth of a Nation, as filmmaker and producer Peter Davis discussed in his presentation about how the film influenced early filmmaking in South Africa.

“Bringing the past into the present gives the film immediacy, and the symposium showed how it continues to resonate both historically and transnationally,” Martin said.

Longer term, Martin said the proceedings of the symposium will be available for scholars and students. The fall 2016 issue of Black Camera, the journal Martin edits, will likely feature one of the two keynotes and paper or two from the proceedings. And the entire proceedings will be published in book form by fall 2017, by Indiana University Press or another university press, Martin said.

— With reporting by Sam Robinson

More: