Research fellow sifts through Vieyra archive for hidden gems

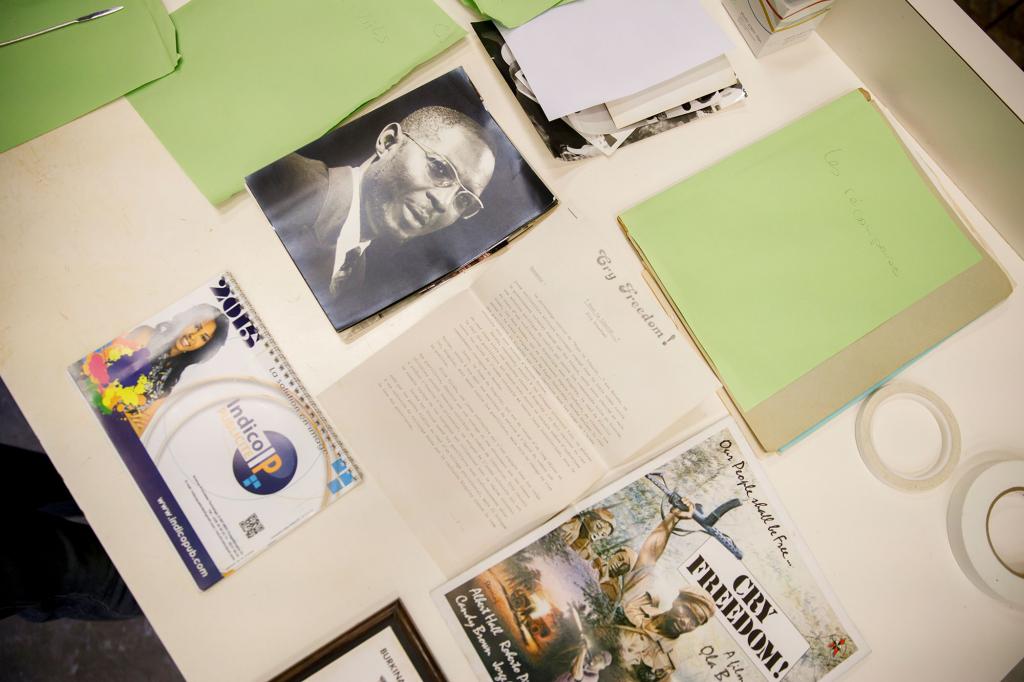

Among boxes of manuscripts, screenplays, photographs, films and audio recordings once owned by seminal African filmmaker Paulin Vieyra, research fellow Vincent Bouchard unearthed unpublished books that provide new insight on African cinema.

Bouchard, an associate professor of French and Italian, has been sorting through the Black Film Center & Archive’s newly acquired Vieyra archive. With his French language expertise and extensive research in West African cinema, Bouchard is uniquely qualified to work in the collection.

Vieyra was the first French-speaking sub-Saharan African to direct a film, 1955’s “Afrique-sur-Seine.” He was a pioneering critic, historian and producer during the decolonization era of the 1960s, and he was a mentor to Ousmane Sembène, known as the father of African cinema.

Vieyra’s son, Stéphane Soumanou Vieyra, donated the archive to the BFCA this summer.

Vieryra wrote several books and was preparing a second volume for two, one about Sembène and the other on African cinema. Bouchard hopes to turn the drafts into a critical condition book with the unpublished material integrated.

Through this collection, Bouchard has been able to learn more about Vieyra’s legacy and the history of African film.

“We don’t know exactly who he is. That’s what’s interesting,” Bouchard said. “He was kind of forgotten by the main African history.”

The collection has also given Bouchard and other researchers a better understanding of how difficult it was to create movies during this time. They have been able to see exactly how little equipment there was, as well as scant funding.

“The good thing with these archives is that we have very precise data about how French-speaking African films were created,” Bouchard said.

Vieyra was one of the first African people to create movies in Africa. During colonial times, African people were not allowed to film themselves. Vieyra was sent to France when he was 10 to receive an education, becoming one of the first African filmmakers trained by a European school.

“It was a huge opportunity and a big loss,” Bouchard said.

Outside of filmmaking, Vieyra was also a director of cinema, historian, producer, scholar and more. The archives are providing new details on his collaborations, such as those with other African filmmakers, the then-newly founded Senagalese state, international organizations such as UNESCO, film festivals and filmmaker organizations.

The process to acquire the collection took nearly three years. Vieyra’s wife, Myriam Warner, held the papers until she died. They were then held by their son, Stéphane, who had been looking for a place to legate the papers since 2000. Originally, Stéphane hoped to donate the papers in France, but he never found anyone to take them. He then looked in Senegal, but the infrastructure did not support a safe place to keep the papers. When he began looking within the U.S., he was referred to the BFCA.

Meanwhile, Bouchard had been trying to access these archives for 15 years. The match was serendipitous.

The implications of this acquisition are profound for researchers of African film, and the archive will be open to others once the materials have been sorted through.

“For teaching, it’s very important because we will be able to give a more precise view,” Bouchard said. “We hope to have graduate students working on this and create a new movement in African film history of young scholars looking at this data, and trying to bring a fresh point of view on African film history.”