Media School takes on fake news, media distrust

As charges of “fake” news and the idea that media professionals are not to be trusted have become national topics, Media School professors and students are discussing them right along with the rest of the country.

While professors and instructors are weaving the issues into their curriculum, the school also is developing panel discussions and other events open to campus and the community as platforms for conversation.

These initiatives are part of a broader effort to promote media literacy, to help both students about to enter these professions and the news-consuming public navigate the new media terrain.

“Fake news is a new name for something that’s been around for a long time,” said Dean James Shanahan. “But the problem has gotten worse. This is a period in which the country needs to decide who is and who isn’t a reliable source.”

Speakers address “fake or fact?”

The school partnered with IU Provost Lauren Robel’s Hot Topics series for “Fake or Fact? The Search for Real News in 2017,” an open discussion Feb. 9 featuring speakers who outlined the issue, then offered tools for defining fake news.

Social media has provided the easiest channel for the propagation of fake news, said Filippo Menczer, a professor of informatics and computer science at IU. He showed the audience a series of algorithmic graphs displaying how efficiently social media spreads information, no matter if it’s fake or true. He also explained that social media users are both victims and perpetrators when false information becomes “common knowledge.”

“We all live in these echo chambers, we are surrounded by people who think like us,” said Menczer. “What you see, what you’re exposed to, is largely determined by the structure of this network. This biases the view of the world that you have and this also makes you more vulnerable to sharing misinformation.”

In a way, Menczer explained, the spread of misinformation is inevitable due to the way the network is set up.

“These networks are organized in such a way that information travels very, very fast. So, if one person shares something, many, many people will see that information,” he said. “Not only that, but many people will see it coming from many different sources. And we are more likely to believe something if it comes from multiple people because our innate bias is to believe that our friends are good sources.”

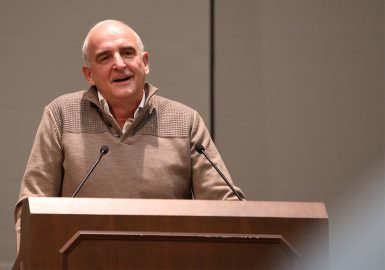

IU’s Poynter Center Chair Roger Cohen, a columnist at The New York Times, spoke in a broader context but also defended legacy news organizations, such as his newspaper, which the current administration has claimed are “failing” or “lying.”

“When you have emanating from the highest office in the land, almost every day, things that are totally untrue or partially true, this seeps into the culture. This is almost like lying becomes OK,” said Cohen, who related stories of his colleagues who had risked and even lost their lives reporting from war zones. “I feel a great surge of anger when I hear this trite dismissal of what we do, sometimes at great risk, as merely fake news. Again, the fake news is coming from the other side, it is not coming from The New York Times or The Washington Post.”

Cohen said this behavior is not only troubling morally, but also is dangerous.

“When the distinction between truth and untruth disappears, when people are manipulated and we lose our bearings, when we’re disoriented, when we’re down the rabbit hole, all kinds of very bad things can happen,” he said.

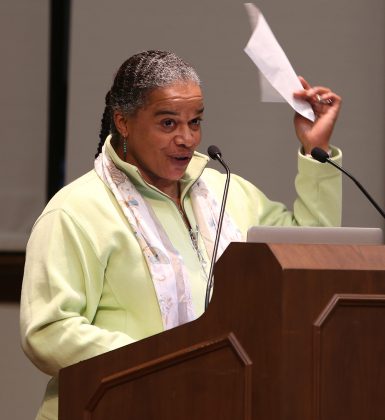

The last speaker, Caryn Baird of Politifact and the Tampa Bay Times, suggested tools to assess facts, to find original documents and to discern if documents are trustworthy. She uses these tools in her own work as a researcher supporting reporters at those news organizations.

In addition to digging for truth, Baird urged her audience to avoid their bubbles, to watch and read news – and social media channels – that represent all perspectives.

“As journalists, you’re not supposed to have any opinion,” said Baird. “Expand your reading list. You might get a better understanding of your neighbor.”

Earlier in the day, a panel featuring Cohen and student journalists discussed ways to deal with the 24/7 news cycle, a phenomenon that often prevents journalists from taking enough time to weigh the leads and news coming from other sources, social media and the public. Working too quickly to fact-check or track down the origins of news also has contributed to misinformation in media, they said.

In the classroom

In classrooms, professors are drawing on their own experiences to give context to the issue, and they’re also making sure their students are listening.

“Traditional journalism involved taking great pains to separate fact from fiction,” said Anne Ryder, a long-time television news journalist and visiting lecturer at The Media School. “I’m afraid that in the push to get it all out fast, we are losing that. The media is partly to blame. We didn’t prepare our young journalists to feed the beast.”

Associate professor Emily Metzgar said media literacy, the ability to understand the origins of news and social media posts, is important for news consumer and for those producing news. Student journalists must be aware of how they are constructing, or framing, their stories.

“Framing is like cropping a photo,” she said. “You are making a decision of what to leave in and what to take out. It’s not evil, it’s a necessity. It’s important to recognize that by zeroing in and ignoring some parts of the story, you are choosing what to present to the world. And that has consequences.”

In her own classroom, Metzgar has taken steps to being as objective as possible and not frame the discussions or lessons around her opinions. She said she’s trying to tackle the “fake news” phenomenon as she’s always approached her teaching.

“I’m reluctant to use the term too often. I try to be as middle of the road as I can be, particularly when I teach,” said Metzgar. “It’s important as a teacher that no student feels mocked for what they believe. I, of course, don’t want to provide a safe space for hateful language, but I think it is important to be able to speak openly.”

Next steps

The school plans to continue topical discussions to address these issues and educate students as well as members of the broader community. Next up is a panel, “Cybersecurity for Journalists (and Everyone!)” Feb. 23

The panelists will address ways journalists can protect their sources and sensitive information from hackers and surveillance, “which could be useful for the rest of us to know, too,” said associate professor Anthony Fargo, one of the organizers.

Panelists include Nate Cardozo, attorney for the Electronic Frontier Foundation; Susan Sons, senior systems analyst for the IU Center for Applied Cybersecurity Research; Marisa Kwiatkowski, investigative reporter for The Indianapolis Star; and Fargo, who also directs the school’s Center for International Media Law and Policy Studies.

This is the first event funded by a gift from Barbara (Blackledge) Restle, BA’72. The Barbara Restle Press Law Project will be implemented by the school’s Center on International Media Law and Policy and will support research, public lectures and travel for research purposes.

Restle said in an earlier press release that her gift was spurred by recent developments in the arenas of journalism and politics, in which she has seen news programs become more politically slanted

“From my point of view, freedom of the press is really being challenged at this point,” she said.

In addition to the biases she observes in current affairs reporting, Restle said the rise of social media and fake news poses further threats.

“In my lifetime I have never experienced the stresses our American journalists are facing today,” she said.

To Roger Cohen, such efforts are crucial for the public and for journalists, both professional and student.

“Journalism has never been more important,” he said. “This is, in short, a very challenging time. But there is also a strong and concerted attempt on many fronts to fight back.”

More: