Martin book contextualizes ‘The Spook Who Sat by the Door’

“The Spook Who Sat by the Door” tells a story that urges people on the periphery, those who have been dismissed as disposable, to take their rightful place in the active transformation of society.

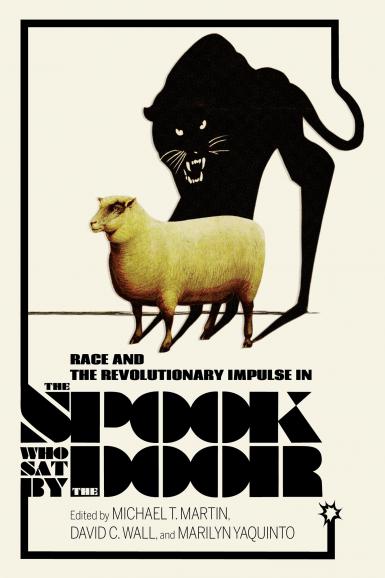

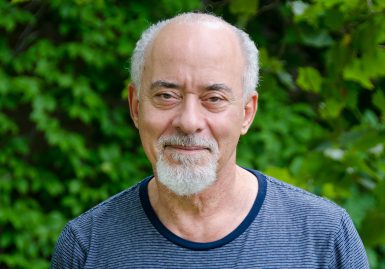

Media School professor Michael T. Martin‘s book, “Race and the Revolutionary Impulse in The Spook Who Sat by the Door (Studies in the Cinema of the Black Diaspora),” co-edited with David C. Wall and Marilyn Yaquinto and published by IU Press, positions Sam Greenlee’s novel-turned-Ivan Dixon film (1973) into its social, political and cinematic contexts.

Media School professor Michael T. Martin‘s book, “Race and the Revolutionary Impulse in The Spook Who Sat by the Door (Studies in the Cinema of the Black Diaspora),” co-edited with David C. Wall and Marilyn Yaquinto and published by IU Press, positions Sam Greenlee’s novel-turned-Ivan Dixon film (1973) into its social, political and cinematic contexts.

Greenlee’s novel and screenplay tell the story of Dan Friedman, an African American man training in the CIA. He uses his skills and knowledge from his training to return to his community in Chicago and organize members of a street gang into an armed revolutionary insurrection. Martin said the story serves as a statement about the realities of black life in the ‘60s and ‘70s, with the denial of human rights and state-sanctioned violence pushing movements off the ground in urban areas.

Greenlee, as Martin described, was a product of America in the late ‘50s and ‘60s. He was a poet who joined the U.S. Information Agency, a “propaganda arm of the state department,” and was stationed in the Middle East. There he witnessed social political transformations of massive scales.

“Witnessing these decolonization struggles for independence gave him a better understanding of race relations here in the United States,” Martin said. “And that’s all reflected, captured compellingly in my view in ‘The Spook Who Sat by the Door.’”

Greenlee and Dixon presented the politically charged film as an action thriller and a blaxploitation film to earn distribution. The blaxploitation genre fed into black audiences’ desire to see themselves as heroes on screen: competent, decisive, able to outwit white people and their institutions. In other blaxploitation films, the black hero is often portrayed as self-serving, instead of struggling on behalf of his or her community, Martin said.

“It promotes this idea of individual solutions to complex structural problems in society,” Martin said. “That is immensely counterproductive because the problems that black people, Latinos and even poor whites face are not problems that can be solved on an individual basis but have to be solved collectively.”

Greenlee and Dixon used the blaxploitation genre and action-thriller feel as a way to essentially sneak the film into distribution circles. One film critic, Kevin Thomas, called it “one of the most terrifying movies ever made.” Friedman provides tactical maneuvers and explosive techniques all laid out plainly in the film and novel, serving as an almost guidebook for revolution.

“It conjures and gestures a historical necessity for African Americans to mobilize themselves,” Martin said. “And if not, reject liberal integrationist politics and move more towards armed struggle.”

The film arrives at this framework by understanding that the black underclass, including those in prison and prostitutes specifically, are living in internal colonies. The armed struggle by these African-Americans would serve as the vanguard for a larger revolutionary movement that would eventually include white people as well, Martin said. He said the film argues that integrationist policies are just a band-aid and a beguiling of African Americans toward believing in the potential for real social change.

The film was pulled from theaters three weeks after its release. Dixon and Greenlee assert that the FBI pressured distributors to pull the film. Martin said he doesn’t find this surprising.

“The whole country is on fire, and here’s a film that is encouraging resistance: armed resistance.”

What will ignite a revolution in America is the grievances and unmet needs of African Americans, which will lead other disenfranchised groups to mobilize their own movements, Martin said of the film. Martin said this mobilization beyond racial groups and concerns terrified the government, and it still does.

“At its face, (the film)’s about a racialized movement,” he said. “But at its foundations, it speaks to the larger question and the necessity for class struggle in revolutionary terms here in the United States.”

The film’s close ties to the political realities of the ‘70s and the continued relevance in today’s climate are part of what make it a piece of black diaspora cinema. Black diaspora cinema, besides the aesthetic achievement, engages with fundamental inequalities in our society with specific stories that relay the larger experience of people of color.

“These films help us intentionally or not to reflect on our own experience,” he said. “It is that reflection that enables us to grasp our situation, the specificities of our situation, wherever we may be, and perhaps, mobilize us to act individually and then collectively.”

Martin continues his work on understanding and reflecting on these films in his courses, including teaching a graduate course on post-colonial metropolitan cinemas, which looks at race and gender in the immigrant experience in European cinema. He also edits the IU Press series, “Studies in the Cinema of the Black Diaspora,” of which his latest book is part of.

Martin will release his next book, “The Birth of a Nation: The Cinematic Past in the Present,” at the end of the summer. The anthology is based on a conference held at the Black Film Center/Archive in 2015 at the centennial of the infamous “Birth of Nation” film by D.W. Griffith.

Before 2019 ends, he’ll publish a book on Charles Burnett’s film, “Killer of Sheep.”