Malitsky publishes film history ‘companion’ book

A new book edited by associate professor and director of the Center for Documentary Research and Practice Joshua Malitsky examines the history of documentary and nonfiction film through a series of scholarly essays.

A new book edited by associate professor and director of the Center for Documentary Research and Practice Joshua Malitsky examines the history of documentary and nonfiction film through a series of scholarly essays.

“What I thought was necessary was a volume that examined how we write documentary and nonfiction film histories,” Malitsky said. “What are the categories that we use to illuminate some aspect of these works?”

Malitsky’s book, “A Companion to Documentary Film History,” published by Wiley Blackwell, offers just that: less a summative study of the history of nonfiction cinema from moment to moment, movement to movement, but a series of commissioned essays that focus on the way documentary film history is written. The book moves through five sections, each populated with an introduction and a range of contributions by international scholars, covering geographies, authorship, films and movements (featuring an introduction by Malitsky), media archaeologies and audiences.

“The book’s rather dry title could well read, ‘Generative Perspectives on Documentary Film History,” offers University of Oregon professor emerita Julia Lesage in a promotional blurb for the volume. “That is, anyone interested in non-fiction media, especially scholars in related areas, will find exciting new ways to think about the media they use, write about and perhaps make.”

But it is also quite literally a companion to documentary film history, offering analyses of the very study of the medium that can complement an understanding or study of its history.

“It’s sort of self-reflective in that way,” Malitsky said. “It’s looking at how we write these histories.”

As such, it offers an approach to nonfiction film study that can function both as an education – Malitsky already has plans to use selections from it in the courses he teaches – and a deeper dive for scholars already well-versed in documentary history.

“A Companion to Documentary Film History” itself ties into a proliferation of interest in nonfiction film in the past 25 years, Malitsky said. The last five to 10 years, especially, have seen a rise in publications focusing mostly on documentary – especially as an idea, or as a contemporary medium. Malitsky felt the moment needed a deeper dive into the way the study of documentary film is thought about.

Work on the book began between four and five years ago, Malitsky said. With a basic concept for the book locked in, he worked with experts in each of the book’s five frameworks to find leading scholars from whom he could solicit contributions.

“It’s a long process when you do that,” he said. “When you’re not putting together pieces that are written for an anthology, but you’re commissioning brand new pieces.”

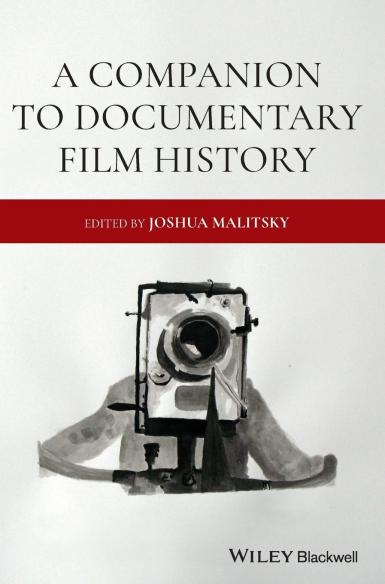

The cover, too, reflects a mode of thinking about documentary, Malitsky said. A painting based on a photograph of a groundbreaking Soviet filmmaker – Dziga Vertov, a figure in both Malitsky’s research and course offerings – it features a man behind a camera, representing loosely a key pair of ideas: that the camera of nonfiction film captures only the real world, and that its vision is still controlled by a figure behind the camera.

“I like this idea of the person sort of hovering behind this big, old camera as a way of thinking about or representing how sometimes people think about the ways documentaries get produced,” Malitsky said.