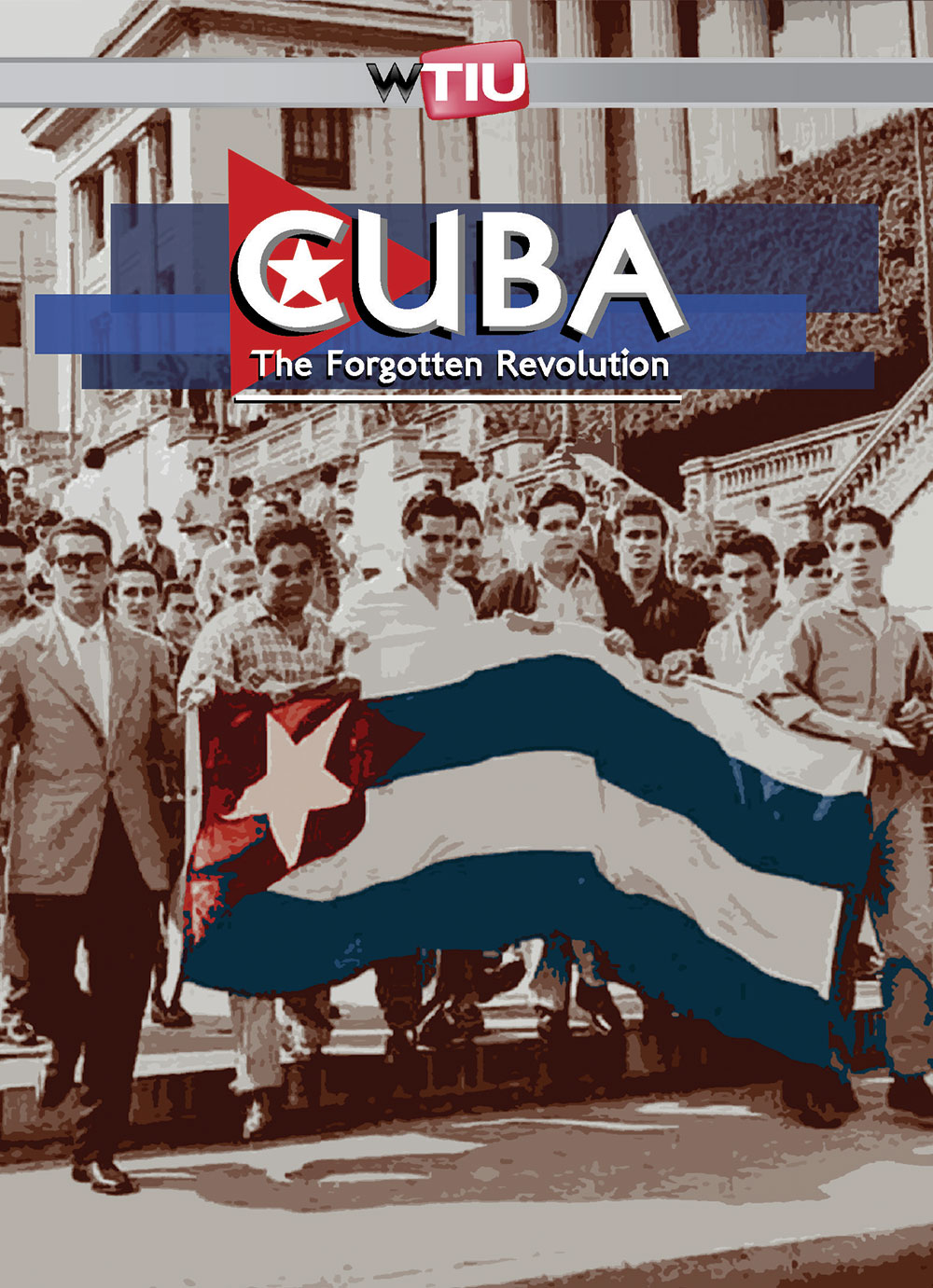

Lecturers Krahnke, Schwibs produce Cuba: The Forgotten Revolution

Two Media School filmmakers are telling another side of the Cuban revolution story through public broadcast.

“If someone tells you that something in history was simple, you can stop listening,” said lecturer Steve Krahnke, executive producer of the film Cuba: The Forgotten Revolution.

Instead, one should look at other sides and for other stories. That’s what he and lecturer Susanne Schwibs have done in their new 90-minute documentary, which airs at 9 p.m. Feb. 16 on local public television WTIU and nationwide in April.

While the narrative of the Cuban revolution is often simplified as the tale of Fidel Castro and Che Guevara, the film focuses on the story of two forgotten revolutionaries, José Antonio Echeverría and Frank Pais. These unlikely rebels -– one an architect student, the other a school teacher — led thousands of fighters in dangerous uprisings in Havana and Santiago.

These actions, the film shows, laid the groundwork for Castro.

“The documentary isn’t to discredit Fidel Castro,” said Krahnke, who also is WTIU’s national program director and has extensive experience as a producer. “It is essentially to correct a narrative, to be more accurate. The way I talk about this to my students is to ‘complexify the truth.’”

The cross-country film project began when a former IU colleague suggested that Krahnke talk to Glenn Gebhard, the film’s director, at Loyola Marymount University. Gebhard had amassed a collection of footage and interviews from Cuba, and had a story idea that might work for public broadcast.

Krahnke immediately thought Schwibs would be a great asset for the project, and they got to work.

“We essentially had to start from scratch, to go back to the original footage and back to the original interviews, and try to tell this complicated story,” said Schwibs, an Emmy Award-winning producer of several documentaries at WTIU.

In total, they put together more than 60 hours of interviews, including some that had never been done, with family members of the revolutionaries, revolution participants, scholars and historians.

“All told, 30 to 40 minutes get into film,” Krahnke said of the editing process. “This is a hard job. And that’s not a complaint, that’s an observation. You have to think very broadly but at the same time very precisely.”

The personal interviews are what make the film, he added.

“What often gets left out of the narrative is the poignancy of the people who are actually making these sacrifices,” he said. “In our film, we talk to their families. We talk to their mothers. We want the audience to realize that these were real people. That’s an example of ‘complexifying’ it. Real people with real ambitions and real futures were dying.”

There was no way the filmmakers could predict that the film’s release would coincide with renewed interest in Cuba. In December, President Obama reestablished diplomatic relations and loosened travel and economic policies with Cuba, policies that had been in place since 1960.

Krahnke and Schwibs are aware that the topic may elicit strong reactions.

“Whenever you do this refinement of history, then you get people who are vested in the story,” Schwibs said. “Once you start messing with even one of the traditional stories, one side will always get riled up. We’re expecting a little bit of blowback.”

Neither Krahnke nor Schwibs had a background in Cuban history, though Schwibs had worked on a film on the 1984 Nicaraguan elections. Combined, the two have more than a half-century of film experience.

Zach Herndon, BA’14, put together the film’s graphics for his former professors. These graphics included lower thirds, animated map shots, the title animation and credits for the film.

“Most of my college film projects ended up teaching me all of these graphics basics. If there’s one thing the IU telecom department excels at, it’s allowing students the potential to use the latest tools and computer programs to make their film ideas as high quality as the ones they see on TV,” Herndon said. “The only difference on this project is that it is actually going to be on TV, which I never thought I would have a hand in so soon out of the graduation gate.”

One challenge when putting the film together was to allow the story to tell itself without framing the narrative.

“I discovered early on that, with a lot of the interviews with survivors of the revolution, they had a limited perspective and I would never use them to draw general conclusions,” Schwibs said. “They’ve experience history different than looking at evidence afterward.”

Instead, the filmmakers presented the evidence and the personal experiences, and they are letting the audience consider the angles and perspectives.

“It’s not whether something has bias or not,” Krahnke said. “It has bias. Our point of view we decided very early on: there are other stories, here are two. We try to mitigate our bias by letting the audience decide.”