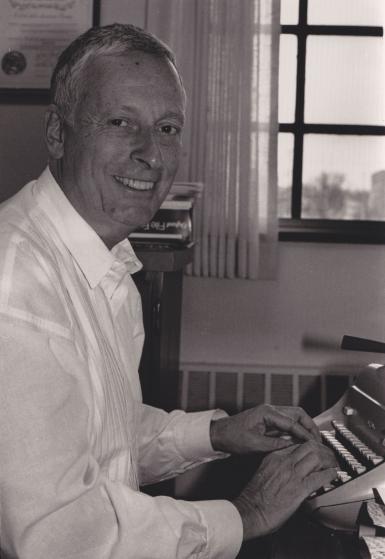

Jacobi remembered for dedication, skill in arts reporting, teaching

When Peter Jacobi returned papers, even the best-scoring writing was covered in edits, recalls Jennifer Tilley, MA’11, arts editor at the Bloomington Herald-Times and former student of Jacobi’s. As a professor, he was keen to make his wisdom accessible to all of his students and to help even the best writers hone their craft to perfection.

Jacobi, who died Christmas Eve, was a hard worker, a passionate advocate for arts reporting and a beloved member of the community.

Two weeks before his retirement, former Herald-Times editor Bob Zaltsberg recalls a then-88-year-old Jacobi telling him he wasn’t allowed. A professor emeritus of IU’s School of Journalism and a longtime arts columnist for the Herald-Times, he’d been a warm presence in the newsroom for so many years that Zaltsberg imagined he’d never leave.

“I just kind of thought he’d be there forever,” Zaltsberg said.

Zaltsberg inherited Jacobi as a freelance writer when he became the paper’s editor in 1985. Jacobi’s impact in Bloomington was huge, he said. Not only in the classical music scene, where his writing was beloved by community members and Jacobs School of Music performers and faculty alike, but also in the fine arts scene as a whole.

“The Herald-Times had no business having a classical music reviewer of Peter’s quality and drive,” Zaltsberg said.

His voice as a writer was informal and friendly, but his wisdom nearly unmatched. His writing conveyed his deep knowledge of classical music without sounding pretentious, said Tilley, who eventually became his arts editor. He was a world-class reviewer to match the world-class musicians he wrote about.

“He demanded that people respect the art of arts writing,” Zaltsberg said.

Zaltsberg once found himself on his readers’ bad side when he tried to reduce the quantity of Peter’s writing that appeared in print. The content would still run online, untempered in length or frequency, but readers were incensed that Zaltsberg would even consider such a thing. A meeting with Jacobs School of Music faculty convinced him that it was sometimes better to leave things alone.

Zaltsberg learned a great deal from Jacobi. He had a steadfast dedication to what he believed in. He understood, and was eager to help others understand, the importance of art in the community.

Plenty of the paper’s staff looked up to him, and though he wasn’t in the newsroom often, they would save their arts and classical music questions for his next visit, Tilley recalled.

“Every area and every beat should have an advocate as strong as Peter was for the arts,” Zaltsberg said.

It was that same dedication and love of the arts that impressed Trevor Brown, former dean of the School of Journalism, when Jacobi came to IU in fall 1984.

“He was deeply committed to effective writing and expression, and a great lover of words and the music of words, which reflects his great knowledge and passion for the arts in general and for music in particular,” Brown said.

Jacobi was knowledgeable, eloquent and deeply passionate about the work he did. As a professor, he was committed to ensuring everyone had access to his knowledge and experience. He was a meticulous editor and commenter, and immensely fond of doing things the old-fashioned way. Even in his later years, he expected drafts submitted on paper, and returned them inked in his wisdom. He assigned so many readings that Tilley devoted a thick file folder to printouts of material he’d assigned.

He was also deeply admired by his students. As dean, Brown read boatloads of student feedback on Jacobi. It was consistently favorable. They admired his dedication to helping them improve and were moved by his passion for the arts. And they were impressed that he was not only teaching them a skill, but actively practicing it on his own at the same time.

“He not only inspired young students, but he inspired young students by his incredible commitment to what he was doing,” Brown said.

He was kind and loved what he did. He kept a collection of favorite paragraphs, phrases and sentences from writers he admired. He was insightful and generous as a colleague. And when he complimented Tilley on her work, she understood how much that meant.

“Peter was always very sensitive — in his writing and his commentary and his own dealings with these writers and performers — to their youth,” Brown said. “They were just starting.”

It was fun and easy to become Jacobi’s editor, Tilley said. He was known for producing pristine first drafts and meeting deadlines. He knew his audience and had a carefully crafted voice. All it really took was removing the Oxford commas he was too fond of.

Tilley continued learning from Jacobi even after transitioning from his student to his editor. He taught her that there is no perfect way to write a story. It can be written and edited and scrapped and rewritten again, and the best way to write it will always be the last one before the deadline.

“Journalism is a living, breathing organism that goes until it stops,” she said.

She also learned from him the power of doing what you love. So did Zaltsberg. So did Brown. He taught it to everyone.

Jacobi, at age 88, told Zaltsberg not to retire for the same reason he stayed in touch with Tilley, planning new columns until the week of his passing. It was his way of life.

“He did not retire from the thing he loved most. He continued doing it to the very end,” Brown said. “A formal retirement does not mean that you have to give up doing what you loved.”

Since his passing, Tilley has received countless emails of appreciation, both for the column she wrote about him and for the work he did as a writer and what it brought to the community.

“He didn’t stop until he literally couldn’t do it anymore,” she said. “I think that keeps people alive longer.”