IU Cinema hosts Naremore, Guy Maddin for 1940s noir discussion

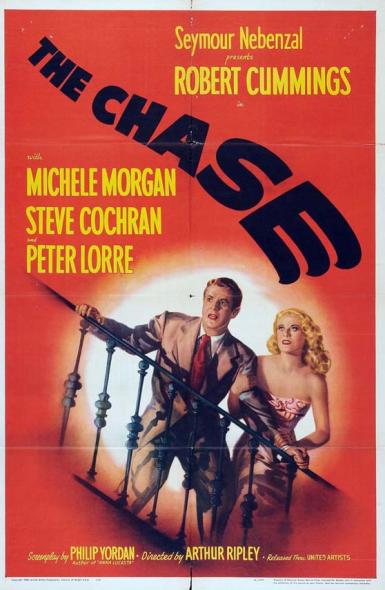

Arthur Ripley’s 1946 noir “The Chase” contains the second-longest dream sequence in a Hollywood noir. Two-thirds of the way through the film, its lead character awakes in a daze, coming to realize that a stealthy escape to Cuba, a romance with a beautiful woman and a terrifying murder plot were fabrications of a gloomy stress dream.

But for Canadian auteur Guy Maddin and Media School chancellor’s professor emeritus (and acclaimed noir scholar) James Naremore, who discussed “The Chase” and more Friday night in a virtual Q&A hosted by the IU Cinema, its real magic lies in the dreaminess of the film as a whole.

Maddin recalls stumbling upon it after finding “perhaps the worst copy ever, on some sort of public domain VHS out of a bargain bin,” he said. He’d heard it praised by a friend who’d been a student of the director, and despite the terrible quality of the tape it was on he found himself watching it again and again. He admired the dreamy qualities of the film — perhaps enhanced by the visual snow that danced across the shoddy VHS image — and assumed because of his copy’s quality that it had been a “poverty row picture.”

Maddin recalls stumbling upon it after finding “perhaps the worst copy ever, on some sort of public domain VHS out of a bargain bin,” he said. He’d heard it praised by a friend who’d been a student of the director, and despite the terrible quality of the tape it was on he found himself watching it again and again. He admired the dreamy qualities of the film — perhaps enhanced by the visual snow that danced across the shoddy VHS image — and assumed because of his copy’s quality that it had been a “poverty row picture.”

“And that excited me because I work on poverty row,” he said.

Naremore’s first experience with the film was similar — a barely remembered first encounter with a low-quality VHS tape in Chicago. But he was entranced, especially by the final scene, which echoes an image from the extensive dream sequence at the heart of the film and suggests an uncertain future that may or may not be as gloomy and fatal.

“It just had such an unreal, sort of dreamy quality to it,” he said. “I was just hooked on the film.”

So when it came time to choose a film for their virtual event, “The Chase” was at the top of both their lists. Naremore — pre-eminent scholar in film studies, driving force behind the creation of the IU Cinema and one of the founding fathers of IU’s film studies program — previously shared the stage at the IU Cinema with Maddin — a wildly inventive filmmaker whose work draws heavily on noir and classic silent film conventions — for a Jorgensen Guest Filmmaker event in 2015. In their conversation Friday night, they joined a Zoom room and chatted like old friends on everything from “The Chase” to “Mission: Impossible.”

“It’s been said for a while now that film is a dream, but some films are more dreams than others,” said Maddin.

“The Chase” is one such dream. It’s a similar experience to watching David Lynch’s surrealist neo-noir “Mulholland Drive,” Maddin said.

Throughout the conversation, Naremore offered nuggets of information on the film’s production. One concerned its transfixing ending. Earlier drafts of the screenplay involved convoluted reveals and a more concrete ending. But because of budgeting issues, the filmmakers settled on an alternate take of a scene from earlier in the film: having fled to Cuba, a man and a woman who is not his wife embrace in the back of a carriage, their future uncertain.

Though still unsure of what to make of it, Maddin had no shortage of love for that ending scene.

Both men also shared their affection for various other facets of the film’s craft. Naremore lauded the work of its cinematographer, Franz Planner, who also worked on “Letter from an Unknown Woman” and “Breakfast at Tiffany’s.”

Maddin took a deep dive into his love for the film’s score, composed by Michel Michelet. When he discovered “The Chase,” the Winnipeg-born artist was yearning to leave home. The only way to do that was often just to listen to the radio. On clear nights, he could sometimes tune into music coming from as far away as Dallas or St. Louis. But that signal was often obliterated by rain. He’d fall asleep to that crackly sound of radio interference layered atop music, and wake up hours later to something clear and entirely different.

The score to “The Chase” seemed to have that same sonic quality, of gentle and dreamy interference. The sort of sound you might hear if you played an old vinyl record and put your thumb on it for a few seconds. Often, it feels like it sits atop a scene rather than defines it, Maddin said. As if someone was DJ-ing the movie in a very satisfying way.

Maddin and Naremore also dove into noir as a genre and what defines it. Since the term for the genre was coined by French critics, it’s been defined and redefined in ways both constrictive and expansive. Some consider it to be all about the iconography; what boxes on the imaginary “noir checklist” are ticked off: Is there a femme fatale? A smoking gun? A private eye? Shadowy tableaus where men smoke cigarettes in the night?

“The Chase” has all of the facets of the original definition of noir, Naremore said, which as translated from the original French definition of the genre relate to its emotional or affective qualities: it’s strange and dreamlike and uncanny, but also uncanny, ambivalent, erotic and cruel.

But Naremore also added that there’s nothing specifically essential to film noir, a topic he expands upon in his 2008 book “More than Night: Film Noir in its Contexts.”

“I’m a Naremorian,” Maddin added. “But what’s essential to me is a dreamlike quality.”

Maddin remembers seeing a few noirs and thinking of the genre as something rigid, relating to the American male contending with postwar realities, his grave already open and just waiting for him to slide into it.

“I was describing a feeling of dread that I got,” he said.

Naremore and Maddin each shared their own recommendations for noirs people might not know or think of as noirs.

Naremore suggested 1951’s “His Kind of Woman.” Maddin offered “Locket,” though he clarified that it might be more gothic melodrama than film noir. He also suggested “Mission Impossible: Ghost Protocol,” calling it a “contemporary noir.”

“Once I started imagining Luis Buñuel sharing a bag of popcorn with me during a Mission Impossible screening I’ve never enjoyed contemporary cinema more,” he said.

On planes, he imagines sharing his headphones with the German director F.W. Murnau (“Nosferatu,” “Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans”) and watching whatever the flight has to offer.