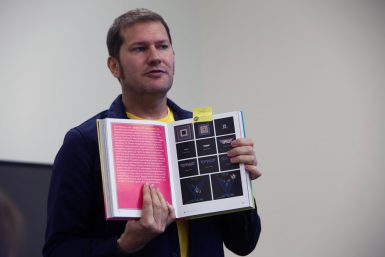

Guins talks on early coin-op game design

Understanding Atari’s coin-op machines requires more than an understanding of the game, according to professor Raiford Guins. Rather, one must take a deeper look at the industrial and graphic design history of these games.

Guins discussed these issues and others addressed in his forthcoming book, Atari Modern: A Design History of Atari’s Coin-Ops, 1972-1979, at The Media School’s weekly research talk Nov. 4.

Atari, the video game founded in 1972, is the focus of research in Guins’ book. He’s considering the design of the coin-operated machines in arcades and how this design impacted the gaming experience.

Guins discussed the need to understand objects in this kind of research, leading to his discovering artifacts and magazines to help his mission. He wanted to better understand concepts of design from the era, so he examined examples of these designs themselves: Coffee pots, consumer electronics, furniture, car design.

“I’ve been buying lots of stuff on Ebay,” he said. “Getting a lot of these old magazines, graphic design magazines, stuff that’s hard to find and many libraries don’t have. I need to see the objects.”

Guins said a review of his own books helped him to better understand his own style of writing and methods of research. He is the author of Game After: A Cultural Study of Video Game Afterlife and Edited Clean Version: Technology and the Culture of Control. He has also served as co-editor of other books on video games.

“I seem to have developed a very particular method when it comes to these books,” he said. “I always try to start by providing a description of things. I often think through things, and I didn’t notice that there’s such an obvious style to this work until I really started to read through and remind myself that I could do these things.”

Guins said this concept of looking at objects as individual pieces of history, using an example of historians looking through drawers to make his point, helped him to develop the organization of his book and the methods he would use to write it and research it.

He described how this method caused him to begin to “think through and with things” and to question what it really means to do research in the first place.

“What is it to do research? Where do you go? Where do you find your objects? How do you make them meaningful in a study or a critique of historical research? Are we getting dirty in the work we’re doing?” he said.

Guins described problems that have arisen in his research and his actions to address them, including the fact that game history is mostly captured in textual analysis rather than “screen essentialism” like design history.

He said a great deal is known about video games, but very little is known about the actual machines designed for game play. To solve this problem, he aimed to track down designers to help make the practices they used in creating the machines meaningful.

He also touched on the need to produce a historical perspective in his writing to embrace the multidimensionality of the artifact.

“I want to go against the essentialist model that only we’re only going to define a game based on code, program platform,” he said. “I’m going to say, ‘that’s right, it’s important, but so is all this other stuff.’”