Game design talk involves audience participation

A presentation on game design turned into an interactive simulation Friday as audience members tried out tools modeling what it’s like to be in doctoral school.

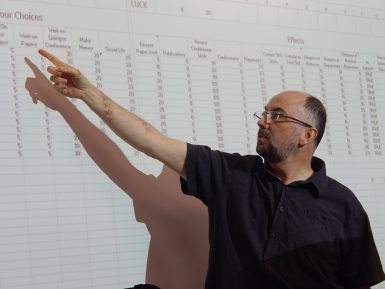

Professor Ted Castronova and doctoral student Isaac Knowles each created a playable graduate school simulator for the event. They then invited volunteers to select their own inputs for variables like producing original research, presenting at conferences and socializing. These choices influenced whether the player would ultimately get an academic job.

Audience members, many of them grad students themselves, were warily enthusiastic.

“You realize this is terrifying,” one attendee said. “Nobody’s going to talk.”

“That’s OK,” Castronova replied. “I’ve been in this business long enough. I can wait.”

While Castronova’s model relied on a familiar program—Microsoft Excel’s formulas function—Knowles employed the online diagramming tool Machinations, which was created by Dutch game designer Joris Dormans. After viewing both demonstrations, the crowd was asked to vote on which one they liked better.

The purpose of the activity was to illustrate a basic premise behind game design: that many contemporary games are made up of complex systems that model real life. The player who fights, quests, earns rewards or loses points in a game is engaging with an intricately engineered system that probably sprang from the mind of a game designer.

Indiana University’s role in this mix is to offer graduate and undergraduate training in game design, a discipline that’s young relative to pursuits like journalism.

“The best people in game design now, they didn’t get degrees in game design,” Castronova said. “They’re learning by doing.”

The benefit of establishing an academic discipline, he continued, is to develop shared theories that encourage people to try new things.

“If there is a general foundation, people can build upon it,” he said.

A spirit of experimentation was apparent even in the two presenters’ demonstrations Friday. While both models performed similar processes, their visualizations contrasted sharply. Castronova’s was nested in the familiar cells and tables of an Excel spreadsheet. On the other hand, Knowles’ was a multicolored, multi-patterned animation of shapes, lines and labels.

As Knowles’ model was running, he could refer to specific aspects of grad student life even as they were being represented on a screen behind him.

“This whole time, there’s stress,” he said, while the interactive simulation moved onscreen. “There’s constantly being stressed. And you have to find ways to manage this stress.”

As Knowles presented his work, another audience member addressed Castronova: “Hey Ted, this is really cool. We’re not voting for your model.”

The quip became truth as Castronova announced the results later: “In a miscarriage of justice, he beat me 19 to 10.”

Friday’s colloquium was part of a regular series in which researchers from the Media School publicly share their work. The program’s curriculum in game design reached a milestone earlier this year as the university approved a request to offer a bachelor’s degree in the subject.