Frenches discuss ethics of premature births

A picture of a baby’s hand clutching an adult’s pinky finger appeared on the screen in the Hutton Honors College Great Room. The hand barely fit around the pinky finger. The baby was about the size of a large mango and weighed just over a pound.

Juniper French was born after only 23 weeks and six days gestation, about 113 days too early. Doctors call this the “gray area.” Babies born at 21 weeks rarely survive, and doctors have a moral obligation to keep premature babies alive at 25 weeks. At less than 24 weeks, the parents often have to decide how they want to continue.

“The doctors put it on us and said you need to decide, and quickly, whether you want your baby to be born. Do you want us to just put her in your arms and let you hold her for however much time she has?” said Juniper’s mother, professor of practice Kelley Benham French. “Or do you want us to hook her up to all this stuff and try to save her?”

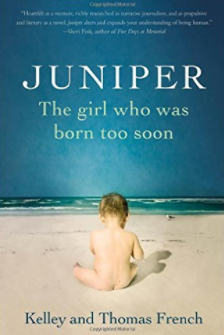

She and her husband, professor of practice Tom French, led a discussion, “Medical and Ethical Decisions for Premature Babies,” Oct. 18, at Hutton Honors College. They focused on the story of their daughter’s premature birth and the decisions they faced during the pregnancy and in the months after her birth. The couple has detailed much of this in their recently published memoir Juniper: The Girl Who Was Born Too Soon, and Kelley Benham French wrote a Pulitzer Prize-nominated series about the experience when she was a reporter at the Tampa Bay Times.

“It was an ethical decision, but it was the most personal decision you can make,” said Tom French. “Are we going to give our daughter a chance, or is it going to be less selfish of us to let her go?”

Medical ethics interlaces every angle of the French’s story, and that is the reason Charlene Brown, director of extracurricular programming at Hutton Honors College, chose to bring the couple in to speak to students.

“We have a longstanding interest in ethical considerations, and we know we have a lot of students on campus who are planning for careers in medical care,” she said. “Providing opportunities for people to think about these kinds of profound questions, we think, has tremendous value.”

The Frenches spoke about the emotional struggles they faced in the hospital waiting for their daughter to be released. How emotionally attached should they get to her? Do they use the name they really like or just the second-choice name? Are they picking their fragile daughter up in a way they won’t kill her?

The possible outcomes of Juniper’s time in the hospital ranged from dying, living her entire life on a ventilator, living a perfectly normal life and everything in between.

The Frenches credit the nurses who were there with Juniper for her survival.

“Every time Juniper was saved, every time she was pulled back from the brink of death — and there were many times — it was because of a human being,” said Kelley French. “The technology and the science is dazzling. No doubt Juniper would not be here if it weren’t for those things, but those aren’t what really saved her.”

They opened the floor to the room filled with many students on track for a medical career to ask questions.

“Obviously, the patient is the primary concern, but how can we be better doctors for the families?” asked Anna Purk, a sophomore studying community health.

The couple suggested doctors speak to families as if they are families and not doctors. Tom French said it is important that families know that doctors do not know everything; they are not gods with every answer.

Students also asked ethical questions about abortion and the money spent on keeping such premature babies alive, questions the parents receive often.

Katie Kapusta is a senior studying journalism and was a student in Tom French’s class during the period the couple was writing their book. She said she learned much from the discussion and from hearing stories behind the book.

“I especially enjoyed hearing Kelley’s side since I already know Tom’s,” she said.

Juniper French, now 5 and in kindergarten, made an appearance near the end of the talk, jumping on her mother and squealing with glee as she heard herself being talked about.

Tom and Kelley French had signed books to sell at the end of the discussion. Included: Juniper’s signature. The letters in her signature are not quite connected, but it is a work-in-progress, her parents said.