Francis book explores prismatic presence of Josephine Baker

Josephine Baker introduced Terri Francis to the world of cinema.

Josephine Baker introduced Terri Francis to the world of cinema.

They “met” in Paris, around the turn of the century — decades after Baker’s death. Francis was researching her dissertation on Black American expatriates in Paris, and Baker was a recurring subject in books and conversations.

“People had been talking to me about her,” said Francis, an associate professor in The Media School and director of the Black Film Center/Archive. “That’s what kind of intrigued me.”

Baker, a French entertainer and civil rights activist, was not initially central to Francis’ research, but she became a key component — Francis’ dissertation was titled “Under a Paris Moon: Transatlantic Black Modernism, French Colonialist Cinema and the Josephine Baker Museum.” Moreover, Baker became both her entry into film studies and a constant presence in her writing and research for the past two decades.

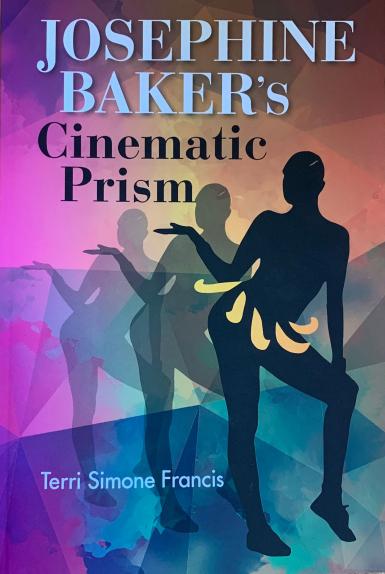

Now, she’s the subject of Francis’ new book: “Josephine Baker’s Cinematic Prism.”

Baker was an accomplished artist, renowned performer and cultural icon. She was a singer, dancer, movie star and avid supporter of the Civil Rights Movement. In 1927, she became the first Black woman to star in a major motion picture. After Germany’s surrender in 1945, Gen. Charles de Gaulle awarded her the Croix de Guerre (military cross) and the Rosette de la Résistance (resistance medal). In 1968, Corretta Scott King offered her unofficial leadership in the United States’ civil rights movement.

To Francis, she was a prism: a lens through which to understand countless other things, but also a powerful artist in her own right whose gleaming surface deserves its own place among the canon of essential Black film artists.

“I just came to decide that Josephine Baker, despite being based in Europe and despite not working with any Black filmmakers, or even actors, or anybody, had this monumental place within the history of Black cinema in the U.S.,” Francis said.

That presence, the focal point of Francis’ new book, was a prismatic one, she said. It was a screen presence, but also a cultural one. Her films and performances were colonial in their images — most famously, Baker donned a few strings of pearls and a skirt of bedazzled rubber bananas for “La Revue Nègre,” a Parisian musical show — but also Black and American because of her presence. And while she was never literally an author in her work as far as writing and directing, she was always the reason for existence, and thus possessed her own distinct authorial command.

“I do see in Josephine Baker a very deep intelligence and a clarity about her own practice,” Francis said.

Baker was deeply committed and a hard worker. She learned to speak French and sing light opera as an adult. She began performing at 15, left America for Paris at 19 and struck up a five-decades-long career that’s still talked about today.

Because of Baker’s sharp versatility, Francis organized her book around the concept of her prismatic image and presence so as to accommodate and motivate all sorts of digressions that deeply enrich the reader’s understanding. In the book’s introduction alone, Baker’s image is expanded and complicated with sections outlining the tradition and channeling of African dance in Baker’s work, the imbricated history of the banana and imperialism, a Beyoncé performance that paid homage to her banana skirt and a discussion of her contentiousness as a subject of academic study.

Subsequent chapters further tackle her status as a transatlantic Black star, coverage of her performances in the American Black press, the colonial images of her dance and film and the complexities of various facets of her work.

“The project of the book is so much to take what seems obvious and say ‘You think you see it, but you don’t really see it,’ because there is this prismatic that needs to be unfolded and described piece by piece,” Francis said.

“Josephine Baker’s Cinematic Prism” is hardly the first of Francis’ writings on Baker, but it might be the last, she says. As an all-encompassing study of Baker, it represents a culmination of two decades of research and writing (from dissertation, through various journal and web publications, to book-length study), as well as thinking.

“It took a while to see her as being all of these things,” Francis said. “I stopped reading into her, I stopped reading through her and decided to look very carefully at what she was doing.”

Francis’ previous writings on Baker are varied in subject and context.

First, she studied Baker as a figure of the Black expatriate experience in Paris, thinking of her as a sort of archive through which to understand more. And it was through that writing and research that she became fascinated with film — an ideal experience in a city of cinemas where everything was showing in countless venues all the time.

Francis wrote about Baker again in an anthology book about different visions of Paris — “Baker was an entrée to think about a particular kind of Paris life,” she said — and again as an example of how to understand Black star studies in “Black Venus 2010.” She wrote about Beyoncé’s Baker tribute and the history of artistic allusions to Baker’s legacy, and about her star status. All the while, her understanding of Baker’s complexity grew toward what it is now.

“The view that I have of her now was not present then,” Francis said. “I don’t think I saw her (as an artist) that way.”

In part, that was influenced by existing literature — Francis’ first encounters with Baker were as a figure briefly alluded to or studied in the introductions or codas of other works. As an example more than a case study herself. She was a sign of colonialist aesthetics here, a symbol of Black success in Paris there. And slowly, in Francis’ mind, she took the form of a prism.

“I was, little by little, centering her in my own work,” Francis said.

That centrality naturally led to an increased focus on Baker’s own agency as a creator and film star, and with “Josephine Baker’s Cinematic Prism,” Francis wanted to assert Baker’s importance as an American film pioneer. While the centering of most Black film studies on America and the African continent — as well as the boundaries of other disciplinary studies — could not quite carve out a particular place for the study of a figure like Baker, Francis asserts the importance of her boundary-defying nature to her identity and significance. She was not undermined by her cinematic reflexivity, but emboldened and enriched. As Francis writes:

“Baker is the authoritative presence in all her work, full stop. That presence is the engine of all of the theories and speculation and attention to her performances over the years.”

“Josephine Baker’s Cinematic Presence” is available through IU Press.