DeGregory describes months of work on long-form narratives

Tampa Bay Times reporter Lane DeGregory has won a Pulitzer Prize, continues to write gripping investigative pieces that capture broad attention, and frequently visits classes at The Media School.

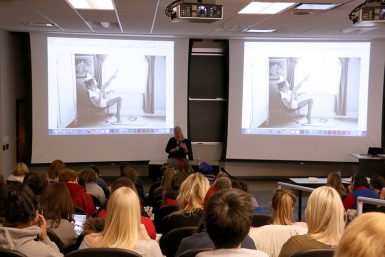

Monday, she was a guest of professor of practice Tom French’s Behind the Prize course, the spring class that invites winners and finalists for top media awards to share their career stories.

“If you ask any young journalist what they want out of their career, they would say, ‘I wanna be Lane,’” French told the students in his introduction.

DeGregory outlined the work flow for her Pulitzer-winning story, 2009’s “The Girl in the Window,” and her path to a career where she’s firmly found her niche.

“I don’t have a beat, so what I try to do is find stories that aren’t really on anyone’s beat,” DeGregory said of her work at the Times. “This has led me to a bunch of stories about foster care and social service issues.”

“The Girl in the Window” grew out of that. DeGregory said every year, the Times’ Metro Center puts out a brief for Heart Gallery, a Children’s Board event promoting adoption. Each year, DeGregory attempts to focus her story on one child as a way to write about the event.

“I think this makes people care so much more about this story in depth,” DeGregory said of telling stories through one person’s experience.

In 2008, the Heart Gallery led DeGregory to Dani, a “feral” child. This is not a diagnosis, DeGregory said, but rather a term from historical accounts of children who have grown up never being exposed to human nurturing.

“It made me realize how rare this was,” DeGregory said. “If I haven’t heard it before, right there I know it’s interesting.”

Police found Danielle, then 7, living in squalor, enclosed in a dark room rank with human feces and crawling with cockroaches. She could not talk, could not walk, was not potty trained and couldn’t swallow solid food. The child was adopted, and DeGregory wanted to know more about the experiences of not only Dani but also the new parents.

But getting this story was no small feat. DeGregory detailed her experience of bringing Dani’s story to life and the importance, as a journalist, of gaining trust and respect with sources.

Dani’s adoptive parents, Bernie and Diane Lierow, initially were opposed to DeGregory writing her story, largely in fear that Dani would be embarrassed or degraded. But with time and support from numerous social workers and board members of the Heart Gallery, DeGregory and her team were able to get a foot in the door.

DeGregory spent six months with Dani and her family. Because of Dani’s lack of communication, DeGregory relied heavily on observational reporting in making the story come to life.

“She was presented like she had severe autism,” DeGregory described.

While communication was a definite hurdle in the formation of the story, DeGregory said that the most taxing part for her was interviewing Dani’s birth mother — the one who left Dani in complete neglect for the first seven years of the girl’s life.

“My editor at the time kept saying she’s Boo Radley, go find Boo Radley,” DeGregory said, referring to the elusive and silent character from To Kill a Mockingbird.

“I tried really hard not to show my anger,” DeGregory said of meeting with the birth mother. “We got there and were totally taken aback. Tears started pouring out of her face under her glasses. ‘My daughter? You’ve seen my daughter?’”

After describing this scene, one student asked if interviewing the birth mother made DeGregory feel bad in any sense.

“I felt like I understood her a little bit better,” DeGregory said. “She gave us all of her documents—medical records, psychological evaluations. Once I started reading through the records, while they didn’t excuse anything, they made me understand her better.”

DeGregory kept in touch with Dani’s adoptive family. After the story’s initial release, DeGregory followed up with “Three years later, ‘The Girl in the Window,’ learns to connect.”

DeGregory’s latest project also follows a story of a child. “The Long Fall of Phoebe Jonchuck,” published in January, details the story a child dropped from a bridge to her death by her father. It took the coaxing of the Times’ managing editor, editor and publisher before she agreed to write the story, which she claimed had been told too many times and had no hope of turning up something new.

DeGregory spent six months combing through piles of public records and interviewing nearly 150 people before she wrote Phoebe’s story. She said each new piece of information she received complicated her story and her writing process.

“People in our storytelling community like to be able to find a single word that describes what the story is about, like ‘redemption’ or ‘revenge,’” DeGregory said. “As soon as I’d think I had the word, my reporting would send me for a loop and I’d be back at square one.”

During a visit last spring to a class taught by Kelley Benham French, professor of practice, Pulitzer finalist and editor for the Phoebe Jonchuck project, DeGregory found her word.

A student remarked that Phoebe’s story reminded her of the novel Chronicle of a Death Foretold, and DeGregory said she realized her story would be a chronicle of the failings and missed opportunities of social service agencies, family and neighbors, and law enforcement that culminated in the tragedy.

DeGregory credits meeting Tom French with her interest in narrative storytelling. She said she first met him at a conference shortly after he won his Pulitzer for “Angels and Demons,” a long-form story about a mother and two daughters murdered during a vacation to Florida.

As a newspaper reporter, she had been writing multiple news stories a day, but was inspired to try her hand at narrative storytelling.

“It was the hugest epiphany to go from being a reporter, a journalist, to being a storyteller,” said DeGregory, who joined the Tampa Bay Times in 2000 and began focusing on this brand of writing.

Reporter Marah Harbison contributed to this story.