Castronova book applies game design theory to life, theology

Plenty of people say that life is a game.

Plenty of people say that life is a game.

It’s usually just a cliche, but for professor Edward Castronova, it became a years-long fascination, and ultimately a book.

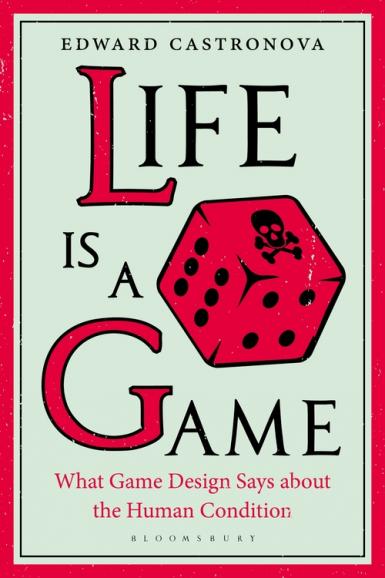

“Life is a Game: What Game Design Says about the Human Condition,” published by Bloomsbury, is the result of Castronova’s deep dive into the thought and philosophy behind that saying, a melding of theological and philosophical ideas with the language and science of game design.

“I thought, ‘Well, we know enough about game design and development now that we can just take that seriously,’” he said.

For some people, thinking about life as a game might reveal some strategic adjustments that need to be made.

Castronova decided to write the book because he realized that so many parts of life bear a remarkable resemblance to games. We ascribe great meaning to menial repetitions of movements and cycles: turns taken, dice rolled, enemies fought, character attributes upgraded.

“You open a box and what you see is a box of atoms,” he said. “I started thinking about how many people really understand that.”

And with so much importance assigned to the grouping of atoms into people and objects and their movements and routines, people still lead lives with great senses of purpose and morality. Castronova thought applying the thought processes of game design to life might help make sense of philosophical and theological complexities.

“I came up with the idea of life as a game to include these different visions and lots of other kinds of stances,” he said.

In the first half of the book, Castronova lays out a basis for his ideas. It consists of three levels of thought and action: the philosophic layer, the strategic layer and the tactical layer.

On the philosophical layer of day-to-day reality, we organize our great philosophical concerns around existing faiths and belief systems; it’s where you place your belief in a higher power or lack thereof, where you label yourself Muslim or Catholic, Orthodox or atheist. On the tactical layer, you make everyday choices: You decide when to set your alarm, how dark to take your morning coffee, how to dress for work. It’s where you do casual thinking and make casual decisions that rarely extend toward the philosophical. The strategic layer, then, is where the other two meet. It’s where you choose to be kind or selfless, if it’s what your faith or philosophy dictate. It’s where, if you believe in conservation or a greener future, you choose to cut out meat from your diet and try to reduce your energy consumption.

The strategic layer, Castronova said, is also where many people might find themselves most closely aligned to others, despite differences in values.

“A lot of people spend more time thinking and fighting about the philosophical stuff with others, when if we look at the strategic layer, a lot of people have the same positions,” he said.

For example, he offered: if an elderly person is having trouble crossing a street, a Buddhist, a Christian and an atheist would all go help her. Because despite their irreconcilable different beliefs in higher powers and states of being, those beliefs all manifest in the same worldly actions.

With those ideas outlined, Castronova moves on to what he calls a person’s “stance,” a combination of the three where philosophical commitments, strategic actions and tactical everyday realities meet in either a coherent or muddled way. Again, Castronova found that game design mechanics provided a model to think about theology.

In the book, he works with the idea of stances to make sense of common combinations of beliefs and actions, and whether or not they make sense. Lots of self-professed Catholics carry out their lives hatefully, he said.

“I’m no theologian,” he said. “I don’t know if that can work theologically, but I do know that from a game perspective that doesn’t make any sense.”

He also notes that if we think of life as a game, then the philosophical layer denotes what the winning conditions are. For Catholics, the goal of the game is to get to heaven, and that’s achieved by living a day-to-day life that adheres to Catholic values.

So for the example of hateful Catholics, Castronova’s critique is less a moral one and more a logical one.

“My critique is not that you’re being a hypocrite or anything,” he said. “My critique is that you’re not going to win the game that you think you’re playing.”

In the second half of the book, Castronova explores common stances and other facets of life that bear a striking resemblance to game design.

One is dynamic difficulty adjustment: a game mechanic where levels and challenges increase in difficulty as the player grows in skill. Castronova said he feels life often operates the same way, where even the strongest people seem consistently challenged by life as they grow and change.

And of course he addresses — but shies away from answering — the big question:

“If so much of life looks like a well-designed game, who’s the designer?” he asks. “I don’t answer that.”