Brownlee preserves stories of emeriti faculty

Even in retirement, Media School professor emerita Bonnie Brownlee hasn’t stopped asking questions.

“What was IU like when you came?”

“What changes did you see over time in the university environment? In research and teaching expectations of faculty? In faculty governance? In the students you taught?”

“What advice would give today to a faculty member who was just getting started in your field at IU?”

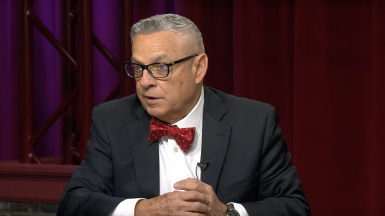

Brownlee is recording the stories of fellow emeriti faculty for IU’s Bicentennial Oral History Project. Launched in 2008, the project has amassed more than 1,200 interviews, which are housed in a database to be transcribed and tagged with keywords. The mission of the project is to record, preserve and make available to future generations the memories and experiences shared. The project includes the histories of alumni, faculty and staff. Brownlee, with Kelley School of Business professor emeritus Bruce Jaffee, collects the stories of emeriti faculty.

Their interview subjects range from close friends to people they know little to nothing about. Interviews generally run for about an hour and take place in The Media School’s Beckley Studio. Often, they follow a similar format — ask how the subject came to IU, ask about campus and the community back then, ask about research and academic work — and they generally end with an invitation to offer advice for new faculty.

“The interviews usually follow kind of a flow chart,” Brownlee said. “But they flow in and out depending on who we’re interviewing and how they want to characterize it.”

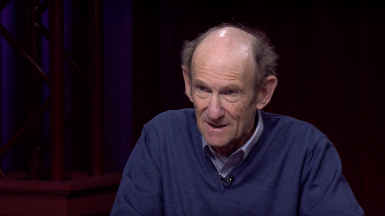

Brownlee and Jaffee inherited the project in 2017 from Don Gray, professor emeritus of English. Gray began conducting interviews of emeriti faculty about 15 years ago, with the goal of painting an oral history portrait of the university going back as far as the 1940s. He interviewed nearly 150 faculty members. His key resource was the Emeriti House.

The Bicentennial Oral History Project’s origins date back to 1970, when IU established its oral history center (now part of The Media School’s Center for Documentary Research and Practice) in celebration of its sesquicentennial. The original project focused on the university’s most prominent figures: administrators, presidents and chancellors of all of the IU campuses.

Decades later, the Bicentennial project aimed to dig deeper.

“We really felt that at this moment in our history we needed to look for other perspectives on the history of the university, in addition to the trustees and others,” said Kelly Kish, director of the Bicentennial.

Gray, who was part of the Bicentennial’s planning committee, had already been doing oral history work since 2005. When the Bicentennial Oral History Project was initiated, it primarily focused on alumni stories. But Gray veered from that path to incorporate his own work with retired faculty into the project.

Many of Gray’s interviews focused on professors’ academic work. He listened to the stories of their blossoming interests as they turned from college degrees to careers. He traced the courses of those careers through changing fields, changing interests and an ever-changing campus. And he always finished the interview by asking if they’d do it all again.

“What we were trying to get, I think, is a picture of what a faculty member did, how it changed and how the students changed,” he said.

While Gray’s initial work focused on interviewing the most accessible retired faculty, Brownlee and Jaffee have tried to seek out women and people of color in order to paint a more holistic portrait of the university, one that honors the richness of its community while also granting voices to those who struggled to fit in or find their place.

They seek out potential interviews from an extensive list they’ve cultivated from annual retiring faculty lists and researching notable retirees from the years before they started the project.

And though it sounds macabre, they have to consider the ages of their subjects so they can be interviewed before their stories are lost forever.

For Brownlee, oral history work seemed like a perfect fit because of its inherently journalistic qualities.

“The idea of recording these stories was intriguing,” she said.

When Brownlee and Jaffee started, they brought some of their own interests into the project. Earlier interviews had been strictly about academics, Jaffee said, but they wanted the project to be more all-encompassing than that.

“That’s valuable, to follow a career,” he said. “We tried to expand it in a couple of ways. One, by expanding the group of people we interviewed.”

They worked to involve more faculty members in administrative roles to explore how the university was run. They also spoke to athletic coaches and tried to explore issues of gender and marginalization, as well.

“What are the barriers, what are the challenges that women or other people faced?” Brownlee said.

With one interview, they tracked the career of Heidi Gealt, a fine arts professor and head of the art museum, as she navigated the male-dominated world of art and curation. Other interviews include Pat Steele, former dean of IU Libraries; Christine Ogan, journalism professor emerita and associate dean of graduate studies in the early days of the then-School of Informatics; and Gerardo Gonzalez, former dean of the School of Education.

Jaffee said he and Brownlee work to maintain an understanding that the interviews are by and for their subjects; there’s no intent to pry, only to give emeriti faculty a chance to tell the stories they want to tell. If he has one regret, it’s that so many of those stories are exclusively positive ones.

“I’d like to get people to be more honest and more forthcoming about problems as well as other things,” he said. “People can say whatever they want.”

While the project is intended to be sprawling and celebratory, Kish said it’s important for it to be more than just commemorative. It has to be honest about the university’s shortcomings and failings.

“President McRobbie, when we first started back in 2008, made it clear that the whole Bicentennial program wasn’t expected to only be celebratory,” she said. “There had to be an element of criticism. There had to be an element of commemoration. There had to be a scholarly aspect to this.”

Jaffee and Brownlee think of the recordings as a resource for future historians. Kish said the Bicentennial provides an important opportunity to ensure that this chapter of IU’s history is recorded and remembered.

“Fifty years from now or a hundred years from now, when people are writing a new chapter of IU’s history about the 20th century, we’ve given them, at least from the late ‘40s through now, thousands of data points that they can draw from to triangulate what they’re seeing in the trustee minutes, what they’re seeing in the president speeches, what they’re seeing in the IDS, what they’re seeing in the yearbook,” Kish said. “They can use these stories to better understand how the university changed and evolved, what the nature of faculty research was, what the nature of student life was.”