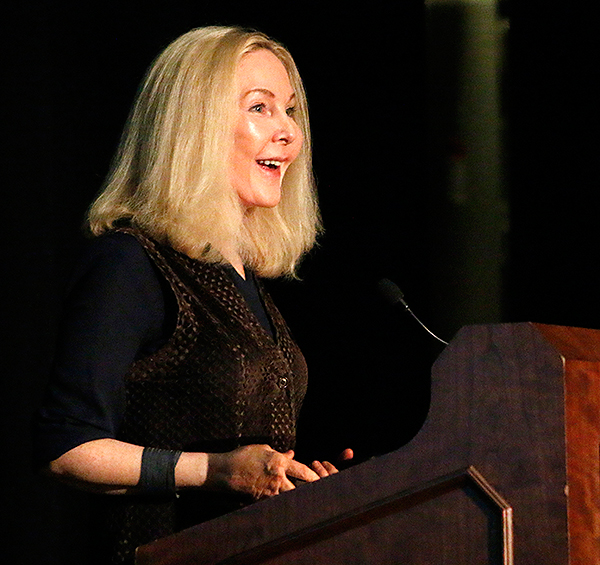

Boo describes process, challenges of reporting on poverty

Indiana and India may be 8,000 miles apart, but the people share common struggles, author Katherine Boo told a crowd in Alumni Hall Thursday evening.

“For all of the increasingly obvious differences between the Bloomingtons and the Mumbais in this world, people are more alike in their ambitions and certainly intertwined in their economic realities than they have ever been,” said Boo, author of Behind the Beautiful Forevers, a nonfiction narrative documenting the everyday triumphs and struggles of Annawadi slum dwellers near Mumbai, India.

Boo described her experiences reporting the book and the outcomes since its 2012 publication as part of The Media School’s Speaker Series. Co-sponsors were the College Arts and Humanities Institute and the Kelley School of Business Common Read Program.

Boo began reporting on Behind the Beautiful Forevers in 2007, splitting her time between Washington, D.C., and India, her husband’s native country. Her goal was not to expose poverty as a moral problem, Boo said. Rather, she had a broader question about poverty.

“What I’m interested in is why is it not more of a practical problem,” she said. “Why don’t the poor storm the gates of the luxury hotels?”

Boo is no stranger to reporting on poverty. Her series for The Washington Post, “Invisible Deaths: The Fatal Neglect of D.C.’s Retarded,” won the Pulitzer Prize for Public Service in 2000. She later joined the staff of The New Yorker magazine, where her article, “The Marriage Cure,” about a state-sponsored program to teach impoverished Oklahomans about marriage, won the National Magazine Award for Feature Writing in 2004. Another article, “After Welfare” won the 2002 Sidney Hillman Award.

But once she began spending time in India, and learning about the culture through her husband and friends, Boo’s reporting instincts took over and she began to think about telling the story of India’s slum dwellers. She said she gave herself six months to see how the reporting would progress, and she spent time in six slum areas before choosing to focus on Annawadi, which borders a sewage pond, a high-end Hyatt hotel and the ultra-modern Mumbai airport.

“I kept returning to Annawadi because it was the most hopeful place,” she said. “Every day in every community I’ve had the privilege of reporting in, low-income people who face seemingly impossible challenges aren’t sitting around and considering themselves doomed. They are thinking, choosing and acting with sometimes astonishing imagination.”

Boo said she knew she wanted to follow the daily lives of as many people in the slum as possible to tell the story.

But this method alone would only constitute what she called “poverty porn.” To completely flesh out the story of the slum in order to represent broader issues, she would need to investigate documents and dedicate an extraordinary amount of time to research and reporting.

“Kate, you’ve got to allow yourself the time, lots of time, to read the documents and to immerse yourself before deciding what your main story is,” she recalled telling herself. “Rushing that decision is a great way of missing what’s really going on in peoples lives.”

It was undoubtedly difficult at first, she said, whether she was observing teenage thieves stealing metal at midnight or talking to a mother raising her children in a hut while dying of tuberculosis.

Furthermore, the petite blonde Westerner inevitably stood out from the crowd.

“I was a freak attraction,” she said. “I’d been walking and I’d turn around and there would be 100 people behind me.” Sometimes, they assumed she was a vacationing American lost on the way back to her luxury hotel.

Under these circumstances, it wasn’t easy to immediately ask her characters to open up. She talked about Sunil, an essentially orphaned 12-year-old trash collector in the slum. She couldn’t tell his story simply by shoving a microphone in his face.

“Sunil’s just going to shrug,” Boo said. “So I have a choice as a reporter. I can decide that what he thinks and feels is unknowable. Or I can invest more time in trying.”

She spent days on end with Sunil, watching him collect garbage and seeing him make choices about the rubbish and his community.

“And then maybe we can start talking about those values,” she said.

For instance, Sunil refused to do something other boys his age were doing: capturing and selling parrots that nested near the slum. With the money from one parrot, Sunil could have eaten well for a week.

“I came to learn that he felt that they’re so few things of beauty in his slum that the things of beauty that were there he felt should be shared with everyone,” she said. “It was a conviction that made him feel different.”

In selecting which stories to tell, Boo said she wasn’t focused on choosing the raciest tales.

“I tend to err on the side of stories of ordinary people that also illuminate something important about the problems of a changing society,” she said. “I’m not a novelist playing with concepts. I’m reporting on real lives.”

Her hope is that reporting on reality will result in uncovering real problems, she said.

“I hope that if I ‘unpile’ a few crimes, that the injustice will become visible and by being visible it might become a little less common,” she said. “When change does happen, it is because people have a very clear sense of the injustice and the humanity of the people affected.”

Her job is to make a reader from anywhere in the world engage with a teenage garbage picker in India, she said.

“If I can’t make a reader see the value of the lives in balance, the problems I’m trying to lay bare are going to be forgotten,” she said.

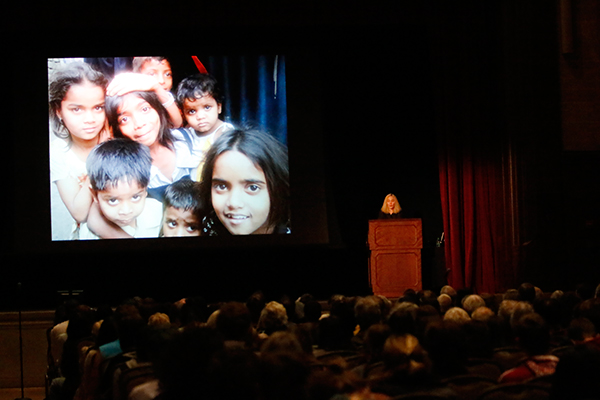

She encouraged readers to think of what they would do in the situations in her book. What would they do if they were Sunil? Or Meera, a young girl who feared being married off? The author posed these questions as their pictures were projected onto a screen.

“I don’t look at the people I’m following just as passive subjects. I see them as active co-investigators of injustice in their society,” she said of interacting with her sources as she tracked their lives. “Annawadi kids know more viscerally than I did what stands between them and their dreams.”

During a question and answer session, local resident Ron Knight asked if Boo had kept in contact with her sources.

“You had these experience with these folks two years ago,” he said. “Do you know how they’re doing now?”

Boo explained that some of the proceeds from her book go back to the Annawadi community, which means she is constantly trying to arrange the transfer of funds. And, yes, she stays in touch.

“The people in Annawadi took real risks to allow their stories to appear,” Boo said. “They thought it was important to bring this book to the page. You don’t just forget that. You just can’t. You just shouldn’t.”

After her talk, Boo signed copies of her book, which was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize and which won the National Book Award.

“I loved her talk. It was so inspiring,” said journalism freshman Brooke McAfee, holding her copy after moving through the line. “It was really interesting how she brought up the importance of empathy over pity. I hope I can reach her level one day.” She showed the inscription in her book: “To Brooke with hope, Kate Boo.”

While interacting with the audience, Boo also emphasized how she was intent from the beginning to keep herself out of the book.

“My perspective is on every page, but there’s only limited amount of space a reader is going to give me for a slum they’ve never heard of,” she said. “I want every sentence that I write in this book to get you closer to somebody you’ve never met before.”

Boo will attend an informal lunch with students at the Hutton Honors College today and speak with journalism students in professor of practice Tom French’s J460 Narrative Journalism and professor of practice Kelley Benham French’s J560 Storytelling classes in the afternoon.

More:

- The Media School Speaker Series continues with guest Carolyn Jones, producer/director of The American Nurse, who will speak at 7 p.m.Nov. 18 at the Buskirk-Chumley Theater. The film will be shown at 5:15 p.m. All Speaker Series events are free and open to the public.