BFC/A’s Norman collection holds artifacts of early Black representation in film

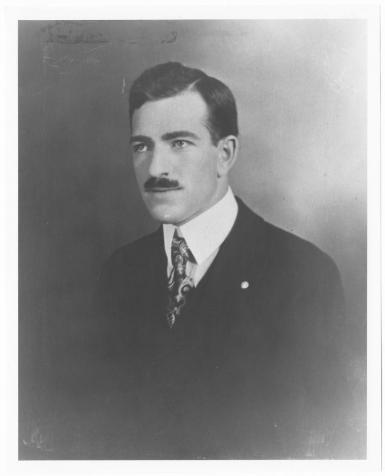

Richard E. Norman made everyday people into movie stars.

A producer of home talent films during the early 1900s, he traveled to towns with a camera and script, and recruited people to star in his film. He filmed over the course of a week, and then sold tickets for screenings in local theaters. Community members paid to see people just like themselves represented on the silver screen.

Then he discovered a niche audience eager for representation in film: Black Americans.

Norman was one of the first producers of race films — films that featured all-Black casts, produced for Black audiences. These films depicted Black characters in non-stereotypical roles, which in that era, meant they were usually middle-class and educated.

Norman’s archives, including distribution records, correspondence, publicity materials, posters, censorship materials, fiscal statements and photographs, are held at The Media School’s Black Film Center/Archive, which — like Norman’s race films — seeks to increase representation of marginalized communities.

Amber Bertin, BFC/A archivist, talked about Norman’s collection Thursday in the third of a series of virtual conversations, called Gather, hosted by The Media School.

The BFC/A is celebrating its 40th anniversary. It was founded in 1981 by Phyllis R. Klotman.

“She noticed that archives that existed at the time really weren’t collecting films that were created by and featured Black people, and if they were, they weren’t really devoting the resources or funding to the preservation of those films in the same regards to films that were created by and featuring white people,” Bertin said.

The BFC/A is both a center and an archive, meaning it collects materials and makes them accessible to patrons while also serving educational purposes to promote and discuss Black film.

“A key component of our identity is that we are a reparative archive, which is an organization that is aware of and acknowledges these past and contemporary discriminatory practices and actively works to combat those, both on a systemic level and on a level of daily practice,” Bertin said. “We are increasing the representation and amplifying the voices of groups and individuals and communities that are marginalized within larger societies.”

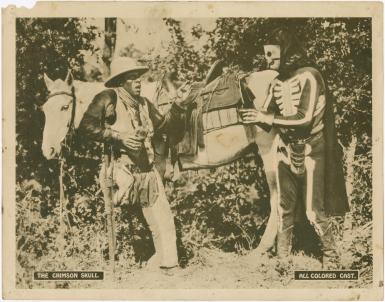

Norman’s Race Filmmaking collection was donated to both the BFC/A and the Lilly Library in 1984 by his son, Capt. Richard E. Norman. Featured in the collection are promotional materials and objects from his films including “The Wrecker,” “The Green Eyed Monster” (which featured an all-Black cast), “The Bull-Dogger” (starring Bill Pickett), “The Love Bug,” “The Crimson Skull” and “Regeneration.”

The only film in the collection that survives in its entirety is Norman’s 1926 “The Flying Ace.” This film follows a WWI fighter pilot who returns home and tries to solve the mystery of a missing payroll master and the $25,000 payroll. It was produced at a time when it was impossible for a Black person to serve in the Air Force.

“This film depicted something that did not exist at the time,” Bertin said. “And we know that it was incredibly popular with audiences and it was incredibly inspirational, because in interview after interview, the Tuskegee airmen who were the first Black fighter pilots who served in WWII referenced this film as an inspiration for why they decided to pursue aviation.”

One of the main reasons Norman was so successful was because of the many Black collaborators he worked with, such as Pickett, Anita Bush, Steve “Peg” Reynolds and Laurence Criner.

Bertin said archives are institutions that replicate and duplicate any discriminatory issues of the society that they existed in.

“Because at their core, archives and institutions that are created by societies in order for that society to tell the story of itself to itself. If that is the case, we cannot separate the archive and the society that it exists in,” Bertin said. “So if you see systemic racism within a society, you’re also going to see systemic racism within the archives that exist within that society.”

Visit archives.iu.edu to learn more about the BFC/A’s collections, as well as its audiovisual and photographic materials.