Auletta describes ascent of Google, implications for media

By Jessica Birthisel

The Googles of the world see nothing but opportunities.

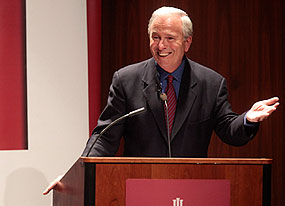

This is how best-selling author and journalist Ken Auletta summed up the success of the company he researched for two-and-a-half years for his latest book Googled: The End of the World as We Know It. Auletta, author of numerous books and articles about media and technology, spoke Monday in the Whittenberg Auditorium, the final visitor in the School of Journalism spring Speaker Series.

Auletta used an anecdote from a 1998 interview with Bill Gates to kick off his talk about the search engine company that continues to expand into communication and media. When asked what he most worried about, Gates said his fear was of someone sitting in a garage, inventing a technology he’d never thought about.

Little did Gates know that that very year, two guys were in a garage, inventing what would become one of the most innovative technology companies in modern history: Google.

“That technology, and all the things Google now does, has in fact become Bill Gates’ worst nightmare,” said Auletta.

But it’s not just Microsoft that’s been affected by Google’s success and unusual business model. The world of traditional media has changed as a result of Google’s reorganization of information. As Auletta describes it, Google made sense of what was at the time a “confusing blizzard of Web sites” and unorganized information.

“What Google did, and this is a miracle, it made it accessible, not just available,” said Auletta, describing Google as “a library at our fingertips.”

Google’s influence goes far beyond Web users looking for information. Auletta said the company has radically altered other areas of knowledge and communication.

First, he described its effects on education, especially in developing nations where infrastructure remains too costly for the average citizen to utilize. Citizens instead use low-cost mobile phones to access the Web.

“People in African nations, school children, are using Google as their text book,” said Auletta. “If you’re in a third world country, it becomes a miracle for you.”

Another practice that sets Google apart is its attitude toward consumers and advertisers. While other early Internet companies such as Yahoo and America Online were devising strategies to keep consumers on their sites for as long as possible, Google’s model “chased people off the site” and got them to where they wanted to go in record time — 0.4 seconds for the average search, said Auletta.

“They understood…this would build up user trust,” he said, telling the story of the young, broke, idealistic Google founders Sergey Brin and Larry Page refusing a $3 million offer from Visa to advertise on Google’s notoriously uncluttered homepage.

To date, Auletta said Google has made $22 billion in advertising revenue, but part of its success lies in honesty with advertisers, who pay for Google ads only when users click on them. This funding model has been a success, though Auletta says it’s struck fear in the hearts of advertising agents, travel agents and other types of industry that rely on more old-fashioned funding models.

Auletta said other companies, particularly media institutions, can learn from Google’s focus on efficiency. He outlined three mistakes

made by traditional media but avoided by Google.

First, he argued that unlike Google, traditional media companies failed to properly utilize engineers.

“The engineers who worked at traditional companies… they were in a box, way down in the totem pole and had no contact with the CEO,” said Auletta. “In many cases, the CEO had no contact with the digital world at all. The world was happening at great speed, and they are not being serviced by engineers.”

Second, Auletta said traditional media companies suffered from what author Clayton Christensen describes as “the innovator’s dilemma.” When faced with an up-and-coming technology, established businesses are faced with a decision: do they hold steady and do what has always brought them success, or do they divert funds in order to compete with the latest techniques and technology?

It’s tough to jettison the very business that brought you success and continues to generate funds, said Auletta, explaining that traditional media, to their detriment, waited too long to react to the changes in user experience and technology.

Finally, Auletta said traditional media practitioners tend to be pessimists, which hinders growth, change and development in the industry. Google serves as a contrast, he explained.

“There’s a lot of idealism at the Google campus,” he said. “They’re fixated on the idea of making things easier for consumers.”

Though Auletta argued that Google has successfully changed the world, the company is not left without its own challenges ahead, particularly online copyright issues, broadband Internet regulations and government intrusions, such as China’s recent ban on Google.

“Brilliant engineers are not always brilliant about things they can’t measure,” said Auletta. “These are huge challenges to Google.”

Google also suffers from a disconnect from the processes of other industries. After a Google executive asked Auletta why he wouldn’t just post his book for free on the Web in order to get more readers, Auletta had to explain that to do so would slash his income, make travel for research unaffordable, and would leave him without editing and marketing support.

“What did I learn from that experience?” Auletta asked rhetorically. “What I learned is this brilliant, young, idealist man…didn’t understand anything about the book publishing business. He’s flying up here at 30,000 feet and doesn’t understand the reality that the writer, publisher, go through. It also told me that this man had a bias about the issue of copyright.”

Auletta rejected the notion that the Internet is the most transformative technology in history, but he did say what is unique about this technological moment is the rate at which change is occurring. This speed, he explained, contributes to “the innovator’s dilemma” and tends not to work in favor of many businesses, such as newspapers.

“The speed of change is phenomenal,” said Auletta. “If you live in a world where you know your business can be disrupted – transformed — tomorrow, you’re scared. And if you’re not scared, you’re an idiot. But when people are scared, they often make panicky, stupid decisions.”

Though an author of several books and a columnist at The New Yorker, Auletta said the process of writing this book helped him realize that there are two types of people out there.

“The first are the kind of people who lean back in this blizzard of information,” said Auletta. “They whine, they complain, they say, ‘Google is an evil empire. It’s not our fault, someone else is doing it to me.’ Those are fools who are dooming their companies.”

The other kind of person is the one who leans forward in the blizzard of information and says, “I know this is a scary time, but it’s a wonderfully opportunistic time.”

“Too often, those in the traditional media don’t see opportunities,” Auletta said. “The Googles of the world see nothing but opportunities.”

Attendees had plenty of reactions to Auletta’s talk. Tina Reigeluth said she was a regular reader of Auletta’s work and a regular attendee of the School of Journalism speaker series. After Auletta’s speech, she said that she had a better understanding of Google’s effect on information distribution.

Journalism and music freshman Kevin Golden said Auletta’s discussion of copyright and the Internet especially resounded with him. He said his attitudes of free, online content fall closer to Google’s philosophy than Auletta’s.

“Being a musician, for me personally, I want as many people to hear my music as possible,” said Golden, who said he would be open to giving away his music for free on the Web. “If they hear it, and they like it, then I believe they’ll buy it.”

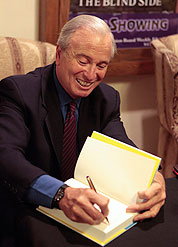

In addition to Auletta’s evening speech, after which he held a book signing, he attended several meet-and-greets during the day with School of Journalism students, faculty and staff.